Remembering Dick Post's life and career

(Download Image)

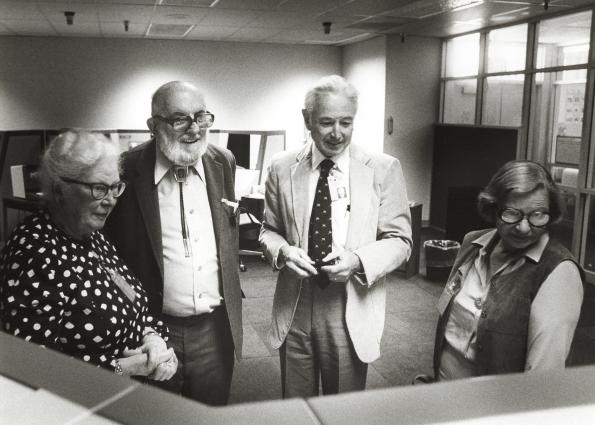

Lawrence Livermore scientist Dick Post had some of the most productive years of his career after he reached 90 years of age — long after the vast majority of researchers retire. Few scientists have had careers as long as Post's. Post joined a national laboratory within weeks of its founding and then worked day in and day out for 63 years — the Laboratory’s entire history. Post, 96, died on April 7 after a sudden illness. Photo by Julie Russell/LLNL

(Download Image)

Lawrence Livermore scientist Dick Post had some of the most productive years of his career after he reached 90 years of age — long after the vast majority of researchers retire. Few scientists have had careers as long as Post's. Post joined a national laboratory within weeks of its founding and then worked day in and day out for 63 years — the Laboratory’s entire history. Post, 96, died on April 7 after a sudden illness. Photo by Julie Russell/LLNL

Livermore scientist Dick Post had some of the most productive years of his career after he reached 90 years of age — long after the vast majority of researchers retire.

Few scientists have had a career as long as Post's. He joined a national laboratory within weeks of its founding and then worked faithfully, day in and day out, for 63 years — the Laboratory’s entire history.

Even fewer scientists can be said to be one of the three founders of magnetic fusion energy research in the United States.

These are some of the achievements of Lab applied physicist Richard Freeman "Dick" Post, 96, who died on April 7 in a Walnut Creek hospital after a sudden illness. His family has scheduled a memorial service for Saturday, May 23, at 11 a.m. at Hillcrest Congregational Church in Pleasant Hill. Lab employees are welcome to attend.

In the words of Lab Director Bill Goldstein: "Dick Post is a legend. His unique contributions to the Lab have spanned its entire existence and enriched our place in history. It was an honor to have known him."

In December 1952, Post joined what was then the University of California Radiation Laboratory (UCRL)-Livermore with a newly minted Ph.D. in physics from Stanford University, after working for a year as a graduate student and consultant for UCRL-Berkeley.

Post, then 34 years old, was attracted to the Lab after hearing at least one of a series of three classified lectures on magnetic fusion that were presented by the Lab’s first director, Herb York, to stimulate interest in the research by potential employees.

"It turned me on, with a capital T, and I wrote him a memo on some ideas I had," Post said in a 1992 Lab oral history. "He (York) simply said, ‘Well, come on out and work on them.’ "

Post was interviewed for a job by Lab co-founder Edward Teller, hired — and the rest is history.

In addition to his magnetic fusion research, Post was considered "the father of the modern flywheel" for energy storage, developed passive bearings and invented a magnetic levitation train system that was licensed to San Diego-based General Atomics.

Post retired from LLNL in 1991 and then within the space of a few months, returned to work, coming in four days a week to continue his scientific research and taking Fridays off because, after all, he was retired.

His career at the Laboratory continued as 11 presidents came and went, and 11 LLNL directors were hired and left. In 2012, he received the Laboratory’s first — and to date only — Lifetime Achievement Award from then Director Parney Albright.

"Dick Post has reached a milestone that is unprecedented at the Livermore Laboratory and perhaps at any national lab," Albright said at the time.

Nine patents after 90

Throughout his career, Post received 34 patents — with nine issued after he turned 90 — in fields such as magnetic fusion, magnetics and flywheel energy storage. Some 85 records of invention have been filed for his research, including one-third of them (28) after he reached 90.

Virtually all of the technologies Post worked on involved energy, and in media interviews he noted that one reason he continued his work was because of the need for energy for mankind and for the country. One of his favorite poems was Edwin Markham’s "The Man With the Hoe," which he said showed man’s struggle without enough energy.

With Post’s work on mirror fusion theories and machines, he was one of three pioneers who created the American magnetic fusion program, according to Ken Fowler, who headed the Lab’s magnetic fusion energy directorate from 1970 to 1987.

The two other magnetic fusion leaders were Lyman Spitzer of Princeton University, who developed the stellarator fusion machine (and was an early advocate of the Hubble Space Telescope) and James Tuck of Los Alamos National Laboratory, who implemented the pinch concept into the U.S. magnetic fusion program.

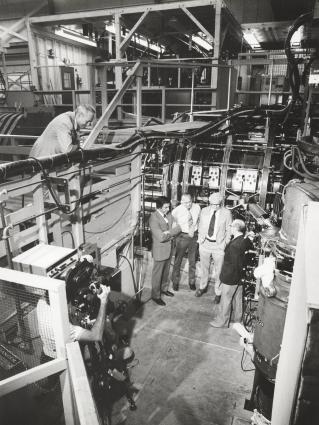

Post contributed three pivotal ideas for the 2XIIB mirror machine at LLNL in 1976 that was the first magnetic fusion experiment to create substantial — and stable — plasma at 100 million degrees Celsius.

His ideas were: 1) the Yin Yang magnetic mirror design, developed with fellow LLNL employee Ralph Moir, that provided plasma stability; 2) the use of 20 kiloelectron-volt neutral beam injectors (built at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory) to create a plasma, with a million times more current than earlier versions; and 3) the theoretical discovery, with Marshall Rosenbluth of the University of California, San Diego, of plasma leakage in mirror machines and the way to stabilize it by cold plasma injection.

After magnetic fusion work was hit by major cutbacks nationwide in the late 1980s, Post undertook research in other areas, such as flywheels and magnetic levitation technologies, but remained active in mirror studies. In 2000, he developed the concept of a "kinetic stabilizer" for tandem mirrors, and today mirror research continues in Russia and China.

Post and Fowler were neighbors in Walnut Creek and carpooled into the Lab together for about 10 years. Their families attended the same church and exchanged Christmas cookies, and Post’s daughter, Markie, baby-sat for the Fowlers.

"Dick and his son Steve loved cars. They bought my VW bug and another VW bug. They discovered the valve stem was overheating in one of the four cylinders and would destroy itself and the engine. Dick and Steve rebuilt the cars with a sodium-cooled valve stem that solved the problem," Fowler recalled.

"One night when we turned the corner from Interstate 580 to 680, one of the wheels went rolling off the car and Dick brought the car to a three-point landing. I don’t even remember how we got home that night.

"When I think of Dick Post, I’m always reminded of the word ‘gentleman,’ and I come from the South, where that term is an extreme compliment," Fowler added.

Focus on flywheels

For the past seven years and during earlier stages of his career, Post focused on developing electromechanical batteries or flywheels for bulk energy storage and for use bridging electrical power interruptions until diesel generators could start.

In 1973, Post and his son authored a seminal article on flywheels that appeared in Scientific American magazine. They proposed that advances in materials and mechanical design made it possible to use large flywheels to store energy and smaller ones to provide power for cars, trucks and buses.

About 40 years later, Post and Bob Yamamoto, now the chief engineer for Z Program, headed a team that worked on flywheel batteries under a cooperative research and development agreement (CRADA) with a Midwest company for several years.

Their aim was to produce a prototype flywheel battery and, although the CRADA ended early, the team advanced the prototype a little more than half way to completion, Yamamoto said. Plans are under way for a new CRADA that would lead to a flywheel prototype for bulk energy storage.

"When we were working on the CRADA, I would see Dick every day," Yamamoto said. "We would generally talk about his latest thoughts on the system’s configuration, the development of engineering from Dick’s theories and ensuring that we got the work right.

"He had ideas all the time. He worked Monday through Thursday, but he often came up with new ideas during his off-time."

Yamamoto came to the Lab after working at Lawrence Berkeley Lab in the 1970s and 1980s with Klaus Halbach, one of Post’s close collaborators, who had developed the so-called Halbach arrays used in flywheel batteries and other applications.

"It has been an extreme honor to work with Dick Post because he was very special in that he understood the need for engineering to be coupled with theory. Dick was extremely energetic. He was like a kid in a candy store, with enthusiasm and excitement that he demonstrated each time he talked about his new ideas," Yamamoto said.

For years, Post kept a small sign in his office that simply said: "It’s the bearings, stupid." Post paid close attention to the bearings, developing passive magnetic bearings that stabilize the flywheel system with negligible energy losses.

By a creative use of magnet arrays, also called Halbach arrays, he found geometries where the bearings would be passively stable, without any need for the complicated feedback stabilization system used for active bearings.

While Post worked with numerous Lab employees, like Fowler and Yamamoto, he also collaborated with scientists from other nations, including a researcher from the then-Soviet Union, Dmitri Ryutov, who now works at LLNL.

Ryutov first "met" Post in 1961 when he was 21 years old and a fourth-year student at the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology — through a book that Post wrote called "High-Temperature Plasma Research and Controlled Fusion," which was translated into Russian.

Later, in 1979, Ryutov and Post actually met in person when they both attended a magnetic fusion energy conference held in Zvenigorod, a city west of Moscow.

"Dick and I got to know each other because we both worked on magnetic fusion energy and we both worked on mirror fusion," said Ryutov, who later was the deputy director for magnetic fusion at the Budker Institute of Nuclear Physics.

"On a weekend day during the conference, Dick and I went cross-country skiing and we each fell about three times and we shared plenty of laughter. What Dick particularly liked about this adventure was watching ice fishermen on the Moscow River," Ryutov said.

Ryutov, a physicist in the Lab’s Fusion Energy Sciences Program and a Distinguished Member of the Technical Staff, joined the Lab in 1994. And, in time, Ryutov joined Post in working on Post’s magnetic levitation train work that won an R&D 100 award in 2004.

"I think Dick is an example of a rare combination of an inventor who comes up with ideas and at the same time is a rigorous physicist. He combined both these lines of creativity. And he was always a gentleman and always respectful."

In 1997, some 36 years after Ryutov first read Post’s book, Post signed Ryutov’s copy of the book in the former Russian scientist’s Livermore home.

Turning to magnetic levitation

Sam Gurol, a nuclear engineer for San Diego-based General Atomics (GA), served as his firm’s director of magnetic levitation systems for 12 years and got to know Post when the firm licensed the Lab physicist’s Inductrack mag lev technology.

GA built a full-scale, 450-foot-long magnetic levitation track and vehicle demonstration system at the firm’s facilities, and Post got to ride on the train in 2005.

"You could only imagine the smile on Dick’s face. He had no problem climbing onto the vehicle and he stood on it and held on. He was 86 years old at the time. He was in great shape," Gurol recalled.

GA had plans to build a 4.6-mile track based on Post’s mag lev technology at California University in Pennsylvania. The state of Pennsylvania had agreed to a funding match and environmental studies had been completed when the 2008 fiscal crisis hit, killing the project.

"I think Dick’s mag lev technology would have been revolutionary because of its simplicity and its fail-safe nature. If there would ever be a failure, the train would stop levitating and land on its wheels," Gurol said.

"I believe that Dick was the definition of a true scientist. He was an academician and a scholar, a renaissance man. He was able to do both theory and experiment and he had a real understanding of how things worked. He could do the math, the physics calculations and the computer programming.

"We had nine companies working on the mag lev and every one of the people in those companies loved Dick Post. During every meeting we had, he had a new idea. He had a profound effect on me and my wife because of the way he lived, his family and the close relationships he had with his family. He was an amazing person," Gurol said.

About 50 years ago, Post gave a tour of one of the Laboratory’s magnetic fusion research facilities to Lowell Wood, who was then a brand new Ph.D. scientist and who would later became the leader of the Lab’s renowned "O" Group for ballistic missile defense work.

"Dick was truly – with zero exaggeration – one of the Lab’s all-time greats, both personally and professionally. He personified – yea, exemplified – what a person of exceptional ability, high integrity and enormous dedication and perseverance could accomplish at a national lab such as Livermore," Wood said.

In the mid-1980s, Lab mechanical engineer Tom Reitter received a phone call from Post because the Lab researcher was going to be attending an international scientific conference in West Germany and wanted to brush up on his German language skills.

Post, who had last studied German at Stanford in 1947, had learned through the Lab’s Technical Information Department that Reitter spoke German.

"Dick suggested we get together for lunch and he paid for the first lunch or two. We became friends and continued to meet for lunch."

Their tradition of Thursday lunches speaking mostly German at a Lab cafeteria continued for about 30 years – up until April 2 of this year, five days before Post passed away.

After Reitter retired in 2007, they continued to meet for lunch, though less frequently, about every five or six weeks.

"We would talk about what he was working on, magnetic levitation trains, flywheels, etc.," Reitter said. "He would bring a German-English dictionary and I would often go over some paragraphs that he had translated from German into English.

"He’s one of the most liked people I’ve ever met. He was very gracious, very friendly and always thinking about other people and ways to help them," Reitter said.

Roots in Pomona

Post was born in Pomona, California, on Nov. 14, 1918 – three days after Armistice Day – and graduated in 1940 from Pomona College, a campus with which his family had more than a century of connections. His grandfather, Daniel Colcord, was a professor of classics, and his mother graduated from Pomona in 1910.

Once Post had his bachelor’s degree in physics from Pomona, he took a job as a graduate assistant there and on Dec. 7, 1941, he was setting up a classroom for Monday’s physics class. He was listening to a shortwave radio he had built and tuned to an amateur band when he heard of Japanese airplanes bombing Pearl Harbor.

Post started to work on sonar at the Naval Research Laboratory outside of Washington, D.C. Soon he was sent on a special assignment to Pearl Harbor.

In a 70th anniversary article about Pearl Harbor published in Newsline on Dec. 7, 2011, "Dick Post: A life in service to the country," Post recalled what happened next:

"Late one night I was rousted out of my bed by a couple of MPs and escorted to Adm. Chester Nimitz' office. I had been called to participate in a conference call over a scrambled line with Adm. Charles Lockwood, commander of all the submarines in the Pacific. There was a problem at our Navy base in Guam and the admiral thought I could help sort it out. And the problem was a doozy.

"A very large and important mission was being planned to attack the Japanese mainland. The attack was a precisely timed strike by 10 submarines under the command of Lockwood and a great number of B-29 Superfortress bombers under the command of Maj. Gen. Jimmy Doolittle. The big problem for the submarines was the route they had to travel to meet their target. The subs needed to pass through the Tsushima Strait to reach the Sea of Japan, and the strait was heavily mined with anti-submarine mines."

In a 1992 Lab oral history with then-Lab archivist Jim Carothers, Post explained the situation: "The problem was that the Navy Lab at San Diego had developed this very special FM sonar gear. They had sent it out, just built in the lab, and all of sudden it was to be put in the submarines and run, and they did not send any technical person with it. So all we had were just the instruction books on this stuff."

Post was then sent to Guam to train the submariners to use the FM sonar gear. "That was an amazing, intense experience. We worked essentially 24 hours a day.

"Their lives were dependent on whether this gear worked. There was no way they could go into that inner sea without this gear. There was no way they could get through if this gear didn’t work."

Post and others put together a paper of technical hints for the submarine technicians, how they could repair certain items, what spare parts could be used, etc.

"The mission was marvelously successful," Post said. "I had a report from the guys when they came back through Pearl Harbor. They didn’t go back to Guam. One of the subs had gone through the mine fields, and had scraped cables on both sides. They had gone right through – here’s a mine, here’s a mine, and they had gone right down between them scraping the wire cables. That was because they could see the mines with the sonar."

Numerous honors

Through the years, Post captured a host of awards and honors. He was a fellow of the American Physical Society (APS), the American Nuclear Society (ANS) and the American Academy for the Advancement of Science.

He was among the first recipients of the APS James Clerk Maxwell Prize in 1978, along with the Distinguished Associate Award from the Energy Research and Development Administration (the predecessor of the Department of Energy), the Outstanding Achievement Award from the ANS, and the Popular Science Design and Engineering Award for "passively stabilized magnetic bearings" in 2000.

In recent years, Post’s story of working at LLNL for 63 years attracted some attention in the media, including the Contra Costa Times and the Los Angeles Times.

While Post continued to come into the Lab four days a week and worked up until the week before his death, outside of LLNL he flew remote-controlled helicopters with his sons, Stephen and Rodney, and had, within the last several years, started taking piano lessons (see video).

In a story published by the Bay Area News Group, his daughter, actress Markie Post, said: "He loved his life; he loved his family and he loved his work. He felt like a blessed man; he never took it for granted. He didn’t have an ounce of bitterness in him for anyone. He had so much humility; I don’t think he knew how treasured he was in the scientific community."

Quick to smile and with a quiet demeanor, Post was very devoted to his wife and family. He met his wife, Marylee, also a Pomona College student, in Washington, D.C. while he worked at the Naval Research Laboratory and she worked at the War Production Board.

They became engaged during the war and got married about two years later, exchanging letters almost every day during those years.

Once married, they often celebrated their birthdays —Post’s birthday was Nov. 14 and his wife’s birthday was Nov. 12 — as a family with trips to Carmel, and one of their favorite family vacation spots was a small village, Wengen, in the Swiss Alps.

After 66 years of marriage, his wife passed away in 2012. He is survived by his children: Stephen Post of Walnut Creek, Rodney Post of Concord, and his daughter, Markie Post, of Toluca Lake, as well as five granddaughters and one great grandson.

"We put a lot of energy and time into the flywheel technology. It would be wonderful if the technology that Dick had worked on for so many years would come to commercial fruition," said his colleague Yamamoto.

Contact

Stephen Wampler

Stephen Wampler

[email protected]

(925) 423-3107

Related Links

Newsline (LLNL employee online publication), “Dick Post: A life in service to the country,” December 7, 2011.News release, “Dick Post receives lifetime achievement award,” October 16, 2012.

Science and Technology Review, “Energy on demand,” April-May 2011.

Related Files

DownloadTags

Industry CollaborationsTechnology Transfer

Careers

Featured Articles