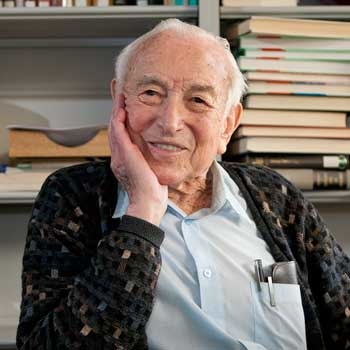

Dick Post: A life in service to the country

On Dec. 7, 1941, Dick Post was at work. He had earned his bachelor's degree from Pomona College the previous year and was spending some time as a graduate assistant, putting together enough money to start his graduate work. On that sleepy Sunday, he was setting up a classroom for Monday's physics class and listening to a shortwave radio he had built and tuned to an amateur band.

Then life began to change.

In 1941, most shortwave traffic was in Morse code, but some people were experimenting with voice over long distances. And that's what Post was listening to: a conversation between Pearl Harbor and somewhere in the United States. The call started off mundane and continued that way, perfect background noise to keep Post company. Until...

..."I heard the guy in Hawaii say, 'Hey, there are a LOT of airplanes overhead...a LOT of airplanes...and they aren't ours. They're Japanese. I've gotta go,' " Post recalls. "I knew something really bad was happening, but there was nothing to do but finish setting up the classroom. After I got home, the family radio was already on and the news was starting to come in."

Two months later, through recommendation from one of his professors, Post started to work at the Naval Research Laboratory outside of Washington, D.C. He worked in underwater sound, which for the Navy meant sonar, and Post excelled. Post was sent on a special assignment to Pearl Harbor and, while he was there, something unusual happened.

"Late one night I was rousted out of my bed by a couple of MPs and escorted to Adm. Chester Nimitz' office. I had been called to participate in a conference call over a scrambled line with Adm. Charles Lockwood, commander of all the submarines in the Pacific. There was a problem at our Navy base in Guam and the admiral thought I could help sort it out. And the problem was a doozy."

A very large and important mission was being planned to attack the Japanese mainland. The attack was a precisely timed strike by 10 submarines under the command of Lockwood and a great number of B-29 Superfortress bombers under the command of Maj. Gen. Jimmy Doolittle. The big problem for the submarines was the route they had to travel to meet their target. The subs needed to pass through the Tsushima Strait to reach the Sea of Japan, and the strait was heavily mined with anti-submarine mines.

The good news was that a highly advanced form of sonar had been invented at the University of California, San Diego. The sonar, called the QLA, was the first sonar to combine aural with visual data and was accurate up to a quarter of a mile -- just right for finding a clear path through a dense minefield. And this was how the submarines were going to cross the heavily mined strait. The equipment was manufactured by Western Electric and arrived in Guam in time to be installed and tested, then the crews were trained on how to use it. That was the good news.

The bad news was that the program to develop the QLA sonar hadn't taken into account how to install the equipment and how to train the seamen who needed to use it. It fell to Post and an ensign to solve all that in time for the mission.

After Post and the ensign arrived at Guam, they spent weeks working day and night. At night, they worked on figuring out how to operate the equipment and, once installed, how to maintain it. During the day, they trained the sonar operators on the new equipment.

"It was stressful, exhausting work," Post said. "I was working in a team of three people, assisted by a lieutenant JG and an ensign. By the time we were done, the ensign had completely stopped talking to people and the lieutenant suffered such a severe mental collapse he had to be flown back to the states. Me? I was so caught up in trying to solve the problem that I had completely lost track of time."

The mission was launched and the pack of 10 submarines crossed from Guam to the Tsushima Straits where they discovered that the minefield was even denser than anticipated. The submarines had to cross through the minefield one-by-one because if one of the submarines set off a mine, it might have exploded the surrounding mines, setting off a chain reaction that would destroy the entire pack of subs.

So, one by one, the submarines crept through the minefield, and it looked like the sonar was performing to expectations. Post later learned one of the subs chose a path that took it between a pair of mines so close together that the cables scraped both sides of its hull as it passed between. Yet all the submarines made it through.

While he was in Guam, Post saw crippled destroyers limp back to port -- out of the war for weeks while they were being repaired. Post found out that a lot of the damage resulted from these ships serving as picket ships for aircraft carriers.

Pickets are ships that sail many miles in front of an aircraft carrier group. Their mission is to spot Japanese aircraft -- or any other threat -- and warn the carrier group so they can prepare.

These picket ships also needed to help fighter pilots from the aircraft carrier intercept Japanese fighters, dive bombers and torpedo planes closing in. Of course, the Japanese were well aware of this tactic and often redoubled their efforts to sink the picket ship, frequently using kamikazes.

When Post returned to Pearl Harbor from Guam, the admiral of the submarine fleet came up with a breakthrough. He proposed to replace the destroyers with a submarine that could spot enemy aircraft and then get below the ocean's surface before those planes could do any damage. The problem was that a submarine didn't have the type of radio equipment needed to serve as a picket, especially when submerged.

Again, Post's familiarity with submarines and electronic equipment was put to good use. Submarines had two periscopes and Post figured out a way to remove the optics from one and fill its tube with the specialized radio gear that could be used even when the submarine was submerged. Post and his colleague, Rex Lovejoy, designed and tested the new antenna rig.

"The Navy needed this idea right away because, as it drove closer to Japan, Japan escalated its use of the kamikaze," Post recalls.

In July 1945, the Navy ordered 24 submarines converted for picket duty. Before the war ended in August, Post was converting the USS Grouper and USS Finback and preparing to see them set sail.

When Post returned to the United States, he started his graduate physics program at Stanford and worked on the university's electron linear accelerator. Following graduation from Stanford, he worked at Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory until Herbert York, the Lab's first director, recruited Post to the Lab to work on controlled fusion about one month after the Lab opened.

"I had to interview with Teller to win the appointment," Post said. "That was a very intimidating experience. Very."

For most of his career at the Lab, Post has worked on magnetic confinement fusion. And for the past few years, Post has been working on magnetic levitation and, most recently, the storage of electrical energy in new, modular flywheel systems.