Former LLNL engineer turned NASA astronaut inspires employees to 'reach for the stars'

(Download Image)

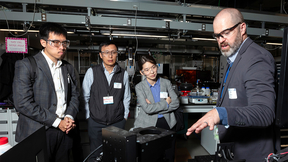

José Hernández toured the National Ignition Facility with another former astronaut, Jeff Wisoff, who is the principal associate director of NIF & Photon Science. Photo by Carrie Martin/LLNL

(Download Image)

José Hernández toured the National Ignition Facility with another former astronaut, Jeff Wisoff, who is the principal associate director of NIF & Photon Science. Photo by Carrie Martin/LLNL

Growing up in the Central Valley, the son of Mexican migrant farmworkers, José Hernández learned early on that education would be his ticket out of a life toiling in the fields. His journey would lead him to a 15-year career at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL), to the zero-gravity of low-earth orbit aboard the space shuttle Discovery, and to a congressional run at the personal urging of President Barack Obama.

Hernández, who returned to LLNL June 4 to speak to employees, said he made up his mind to become an astronaut at the age of 10, while watching the final Apollo mission and seeing astronaut Gene Cernan walk on the moon. Instead of dissuading him, Hernández’ father sat him down and told him what he needed to do to make his dream a reality.

"He must have seen the determination," Hernández recalled. "What he said changed my life. He empowered me to think I could do it."

Hernández’ father presented him with a five-part recipe for success: First, he had to decide what he wanted to be (José already had that part down). Second, he had to realize how far he had to go to reach his goal. Then, he had to draw himself a roadmap, get a good education and use the work ethic he’d learned picking grapes, cherries and other produce to excel in school and in his job. His dad’s last piece of advice was to always do more than what people expected of him.

Putting his father’s advice into action and adding his own step to the recipe -- persistence -- Hernández put his energy into his schooling, earning a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering from the University of the Pacific. He went on to earn a master’s degree in electrical and computer engineering from the University of California, Santa Barbara. He joined the Lab in 1987 to work on applied signal imaging processes, developing X-ray lasers for deployment in space as part of the "Star Wars" Strategic Defense Initiative program. Later, he helped design a digital mammography system for the early detection of breast cancer. His final two years as a Lab employee he spent on assignment at DOE headquarters, working on the Materials Protection, Control and Accountability (MPC&A) Program, where he learned to speak Russian and made numerous trips to the former Soviet Union to help the United States negotiate purchases of nuclear material and help the Russians develop methods to protect their nuclear stockpile. During his career, Hernández also served as president of the Lab’s Amigos Unidos Hispanic Networking Group.

All the while, Hernández never let go of his dream to become a NASA astronaut, using it to drive his career at LLNL while at the same time adding skills and bolstering his resume. Over a period of a dozen years, he applied and was rejected 11 times by NASA before he finally got the call he’d been waiting for his entire life, welcoming him to the 19th class of astronauts in 2004.

"I was so happy," Hernández said. "The Lab was kind enough to put me on leave without pay and said, ‘when you’re done playing, come on back and do some real work.’ "

Hernández took a pay cut from his job as a group leader in the Chemistry & Materials Science Group at LLNL to join NASA at the Johnson Space Center in Houston as an astronaut candidate. It would take two more years of basic training, flight school and practicing spacewalks in pools, followed by another 18 months of flight preparation. Finally, at close to midnight on Aug. 29, 2009, Hernández realized his lifelong ambition, launching off aboard the space shuttle Discovery for a two-week mission to the International Space Station (ISS) as the mission’s flight engineer.

"Once the two solid rocket boosters light up, you know you’re going somewhere because you can’t turn them off," Hernández joked.

During the mission, Hernández played a vital role in docking and undocking the shuttle from the ISS, installing scientific experiments, delivering supplies to the space station and helping his fellow astronauts prepare for spacewalks. The highlight, he said, was seeing Earth from space, a perspective few people have ever seen.

"We were flying over North America and what I saw really surprised me," Hernández recalled. "I expected to be able to distinguish the countries, but I couldn’t make out where Canada ended and the U.S. began, or where the U.S. ended and Mexico began. I had this ‘a-ha’ moment where I realized we really are just one, that borders are just human-made concepts designed to separate us. I wish our world leaders could have this same a-ha moment, and I’ll assure you if they did, our world would be a much better place than it is now."

Over the course of the 14-day mission, Hernández circled Earth more than 200 times, and as he watched the sun rise over the horizon over one flyover, the sunlight hitting the Earth’s surface at the right angle, he noticed something else that shifted his perspective -- the thinness of the planet’s atmosphere.

"What I saw was a scary thing; I became an instant tree-hugger," Hernández said. "I said ‘that’s the only thing that’s keeping us alive.’ I think our environmentalists are correct in saying it’s a delicate balance. If we keep doing things to our planet that affect the environment, we’re going to reach a point where it’s irreversible."

When the space shuttle program ended in 2011, Hernández realized the only way he could return to space would be on a Soyuz with the Russian space program, which would’ve required a commitment to three more years of training, with most of that time spent living in Russia. With five children at home, Hernández decided to retire from NASA to spend more time with them. He also was personally asked by President Obama to run for Congress in the 2012 elections for California’s 10th District, where he narrowly lost to Rep. Jeff Denham, a result Hernández called the "best thing that could’ve happened."

These days, Hernández, who lives in Manteca, keeps busy with his public speaking engagements and private aerospace consulting work with Tierra Luna Engineering. His oldest son Julio, who worked a summer in the Environmental Restoration Division and another summer and fall at the National Ignition Facility, is pursuing a Ph.D. degree in aerospace engineering from Purdue University and wants to follow in his father’s footsteps as an astronaut. He also has two college-aged daughters, Vanessa and Marisol, who are attending Loyola Marymount and UC-Santa Barbara, respectively. A third daughter, Karina, and another son, Antonio, live at home.

Hernández also has written two books, including "Reaching for the Stars: The Inspiring Story of a Migrant Farmworker Turned Astronaut," and started the Reaching for the Stars Foundation to motivate children in the Central Valley to pursue careers in science, technology, engineering and math (STEM).

When asked why he never gave up, even after so many rejections, Hernández said he felt he had nothing to lose.

"I’ve always looked at the glass as half-full and not half-empty," Hernández said. "Every decision I was making to try to become an astronaut was actually helping my career at the Lab. The worst that could happen is I would have a great career (here), which wasn’t a bad consolation prize. The moral is, you’ve got to enjoy the journey."

Prior to his talk, Hernández swapped stories with fellow NASA astronaut Tammy Jernigan, now a senior adviser to the Lab director, and later toured NIF with another former astronaut, Jeff Wisoff, currently the principal associate director of NIF & Photon Science.

Contact

Jeremy Thomas

Jeremy Thomas

[email protected]

(925) 422-5539

Related Links

"Jose Hernandez to lift off aboard Discovery""Lab Engineer Jose M. Hernandez Selected as NASA Astronaut Candidate"

Jose Hernandez Reaching for the Stars Foundation

Tags

EngineeringFeatured Articles