Dead or alive: microorganisms in soil shape the global carbon cycle

(Download Image)

(Download Image)

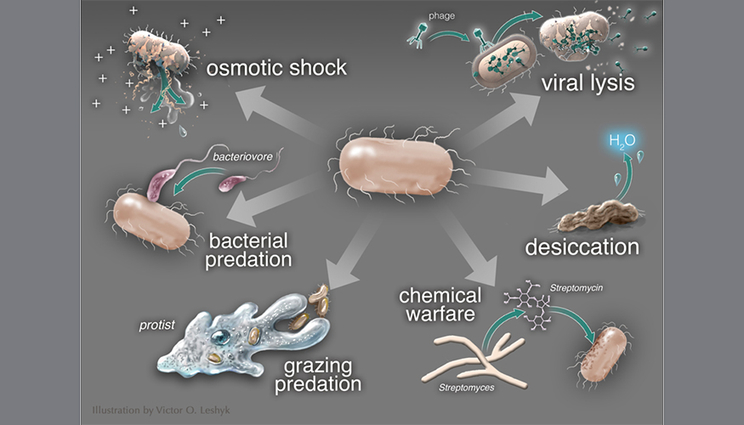

Dead microbial biomass in soil (microbial necromass) forms one of the largest pools of organic carbon on the planet. Different mechanisms of microbial death — such as viral lysis, predation or osmotic stress (shown above) — can influence the chemical composition of microbial necromass and its long-term persistence as soil organic carbon. Image courtesy of Victor O. Leshyk/Center for Ecosystem Science and Society, Northern Arizona University.

Whether dead or alive, soil microorganisms play a major role in the biogeochemical cycling of carbon in the terrestrial biosphere. But what is the specific role of death for the bacteria, fungi and microfauna that make up the soil microbiome?

That is the topic of a new review by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) scientists and collaborators. The article, appearing in Nature Reviews Microbiology, describes how living and dead microorganisms strongly influence terrestrial biogeochemistry by forming and decomposing soil organic matter — the planet’s largest terrestrial stock of organic carbon and nitrogen, and a primary source of other crucial macronutrients and micronutrients.

By shaping the turnover of soil organic matter, soil microorganisms influence atmospheric concentrations of CO2 and the global climate, as well as help provide crucial ecosystem services like soil fertility, carbon sequestration, plant productivity and soil health.

“Our new understanding of how organic matter cycles through soil emphasizes the importance of both living and dead microorganisms in forming soil organic carbon. It is increasingly possible to leverage this understanding within biogeochemical models and to better predict ecosystem functioning under new climate regimes,” said LLNL scientist Noah Sokol, lead author of the paper.

The soil microbiome is the most diverse community in the biosphere, holding at least a quarter of Earth’s total biodiversity. Tens of millions of species of bacteria, archaea, fungi, viruses and microeukaryotes coexist below ground, although only a few hundred thousand have been characterized in detail. A single gram of surface soil can contain more than 109 bacterial and archaeal cells, trillions of viruses and tens of thousands of protists. But the soil microbiome’s influence on biogeochemistry extends well beyond the metabolic activities of living organisms.

“Dead microorganisms accrete in soil as their cellular remains stick to the mineral matrix. Their dead biomass can make up as much as much as 50 percent of the soil organic matter pool. This means that dead microbial biomass in soil is one of the largest stocks of organic carbon on the planet,” said Jennifer Pett-Ridge, LLNL project lead and head of the Department of Energy’s Office of Science “Microbes Persist” Soil Microbiome Scientific Focus Area (SFA).

New advances in DNA sequencing and isotope tracing are allowing the LLNL team to understand the unique attributes of soil microbes — even those that cannot be cultivated in the laboratory. Though analysis of genetic and biochemical signatures, the team can infer the ecological relationships that control who live, and who die, in complex soil food webs.

Because soil microbial necromass (organic material consisting of, or derived from, dead organisms) represents one of the most globally significant pools of carbon and other nutrients, the authors report that the mechanism and rate of microbial death likely impact terrestrial biogeochemical cycling — an idea they are currently testing in a suite of experiments that are part of LLNL’s Soil Microbiome SFA. The SFA team also is establishing experiments to study how different traits of microorganisms affect organic matter cycling in soils. Team members are working to integrate this trait-based approach into models that predict soil biogeochemical dynamics and enhance the ability to predict changes to the global carbon cycle.

Other Livermore researchers include Eric Slessarev, Steven Blazewicz and Rachel Hestrin, and the LLNL Soil Microbiome Consortium, which includes LLNL staff members Gareth Trubl, Karis McFarlane, Rhona Stuart, Erin Nuccio, Peter Weber, Yongqin Jiao, Mavrik Zavarin, Jeffrey Kimbrel and Keith Morrison. The inspiration for this review article emerged from a guided discussion at the 2020 "Microbes Persist" all-hands meeting — highlighting the importance of gatherings where researchers with diverse disciplinary backgrounds are brought together. The work was funded by the Department of Energy Office of Biological and Environmental Research, Genomic Science Program (GSP), which supports LLNL’s “Microbes Persist” Soil Microbiome Scientific Focus Area.

Contact

Anne M. Stark

Anne M. Stark

[email protected]

(925) 422-9799

Related Links

Nature Reviews Microbiology“Microbes Persist”

Genomic Science Program

Tags

Bioscience and BioengineeringBiosciences and Biotechnology

Nuclear, Chem, and Isotopic S&T

Nuclear and Chemical Sciences

Physical and Life Sciences

Science

Featured Articles