Predatory bacteria bite their own

(Download Image)

(Download Image)

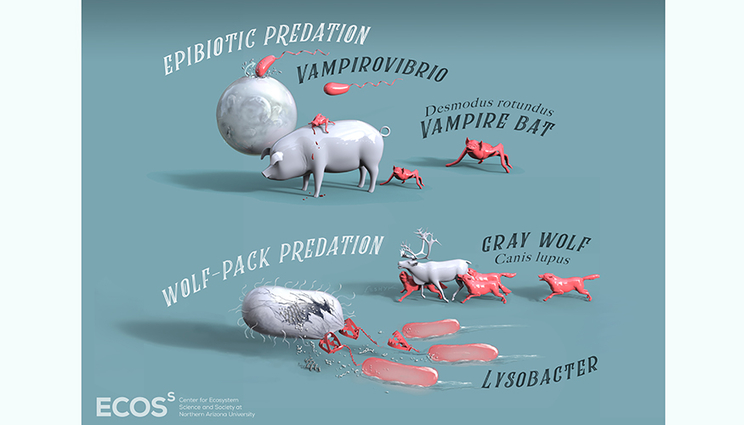

Predatory bacteria — bacteria that eat other bacteria — use approaches remarkably similar to much larger organisms as they target their prey. In the case of Vampirovibrio, the bacterium attaches to the outside of a prey cell and feeds on its interior cytosol — much as a vampire bat sucks blood from mammals it feeds on. For bacteria in the genus Lysobacter, several bacterial cells act as a group to hunt their prey, just as a wolf pack might target an elk. Image courtesy of Northern Arizona University.

Predatory bacteria – bacteria that eat other bacteria – grow faster and consume more resources than non-predators in the same soil, according to a new study by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) and Northern Arizona University.

These active predators, which use wolf pack-like behavior, enzymes and cytoskeletal "fangs" to hunt and feed on other bacteria, wield important power in determining where soil nutrients go. The results of the study, a synthesis of 82 separate studies conducted from more than a dozen U.S. locations and published in the journal mBio, show predation is an important dynamic in natural ecosystems and suggest that these predators play an outsized role in how elements are stored in or released from soil.

The word “predator” may conjure images of leopards killing and eating impala on the African savannah or of great white sharks attacking elephant seals off the coast of California. But microorganisms also are predators, including bacteria that kill and eat other bacteria. While predatory bacteria have been found in many environments, it has been challenging to quantitatively document their importance in nature.

The new study quantified the growth of predatory and nonpredatory bacteria in soils (and one stream) by tracking isotopically labeled compounds (H218O or 13C-glucose) into newly synthesized DNA. Predatory bacteria were more active than non-predators, and obligate predators, such as Bdellovibrionales and Vampirovibrionales, increased in growth rate in response to added substrates at the base of the food chain, strong evidence of trophic control.

“These unique quantitative measures of predator activity suggest that predatory bacteria — along with protists, nematodes and phages — are active and important in microbial food webs," said LLNL scientist Jennifer Pett-Ridge, a co-author of the paper. “We found that growth and carbon uptake were higher in predatory bacteria compared to non-predatory bacteria.”

“We’ve known predation plays a role in maintaining soil health, but we didn’t appreciate how significant predator bacteria are to these ecosystems before now,” said Bruce Hungate, who directs the Center for Ecosystem Science and Society at Northern Arizona University.

The team found that predatory bacteria grew 36 percent faster and assimilated carbon at rates 211 percent higher than non-predatory bacteria. These differences were less pronounced for omnivorous predators (6 percent higher growth rates, 17 percent higher carbon assimilation rates), though high growth and carbon assimilation rates were observed for some facultative predators, such as members of the genera Lysobacter and Cytophaga, which are capable of gliding motility and wolf-pack hunting behavior.

Other Livermore contributors include César Terrer and Steven Blazewicz. Researchers from the University of California, Berkeley, West Virginia University and Pacific Northwest National Laboratory also contributed to the study.

The research is funded by the Department of Energy’s Office of Science and a Lawrence Fellow grant to Terrer.

Contact

Anne M. Stark

Anne M. Stark

[email protected]

(925) 422-9799

Related Links

mBioNorthern Arizona University

Tags

Physical and Life SciencesFeatured Articles