Algae could turn tide of biofuel production

It's not quite like turning lead into gold, but it's close.

Jonathan Trent, a bioengineering research scientist at NASA-Ames, has proposed an ingenious concept for cultivating biofuel-producing algae in the ocean.

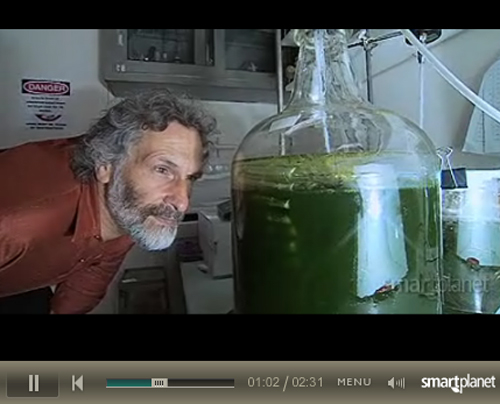

As he explained in a seminar earlier this month sponsored by the Global Security and the Physical and Life Sciences directorates, algae are the best source of biofuels on the planet. "In fact, most of the oil we are now getting out of the ground comes from algae that lived millions of years ago."

In Trent's view, the country needs to develop the next generation of biofuels now because the current crop of biofuels is, in reality, not very green at all.

Biodiesel today is produced mainly from soy, canola and oil palm. The biofuel yields for these crops range from around 50 gallons of oil per acre per year for soy to around 600 gallons per acre per year for palm. Compare this to some species of algae that can produce as much as 2,000 to 5,000 gallons of oil per acre per year.

Further drawbacks of current biofuels production are that it takes large tracts of agricultural land out of food cultivation and, perhaps more important, consumes enormous quantities of water. It takes more than 2,100 gallons of water to produce one gallon of ethanol from corn, more than 14,000 gallons of water for one gallon of oil from canola and a staggering 20,000 gallons of water for a single gallon of oil from jatropha.

"Fresh water is a very limited resource and far more essential to life than oil."

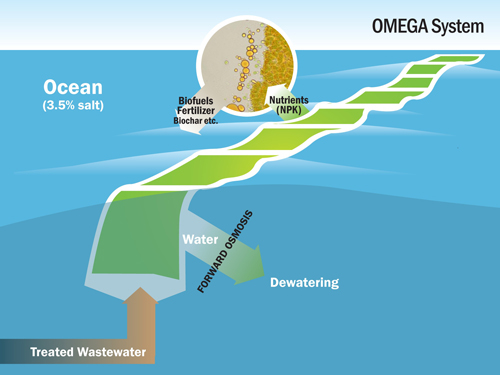

Trent proposes to grow algal biofuels in the ocean, enclosed in large floating structures called "ocean membrane enclosures for growing algae" or OMEGAs.

An OMEGA is essentially a plastic bag with semi-permeable membranes that allow freshwater to flow out into the ocean but prevent saltwater from entering. The clear plastic admits sunlight for photosynthesis. Wave action keeps the contents well mixed, and the ocean itself keeps the algae cultures at a constant temperature.

Treated wastewater would be used to supply nutrients for the algae. Trent envisions OMEGA bags tethered near the sewage outfalls from major population centers so that the wastewater could be piped directly to the algae cultures. "Cities dump millions and millions of gallons of treated wastewater into the ocean. Some of the outfalls are several miles out to sea and others are only a few hundred yards from land."

The algae grow on the nutrients in the wastewater and carbon dioxide from the wastewater and the atmosphere. They can use more carbon dioxide if it can be supplied from coastal power plants or the wastewater treatment process. Growing algae for oil is a carbon-neutral or even a carbon-negative process, depending on how the algae are processed. Algae are very fast-growing, and OMEGA cultures could be harvested roughly every 10 days.

Because the system would use freshwater algae, it is environmentally safe. Even if the OMEGA leaked, the seawater would kill the algae, preventing the escape of an invasive species.

OMEGA is an integrated system that meets multiple needs. In the process of producing large quantities of biofuel, it cleans up wastewater, recycles nutrients, helps revitalize the dead zones that often occur near sewage outfalls and sequesters large quantities of carbon dioxide in algal biomass. In addition, after the algal oil is removed for fuel, the remaining biomass can be used for fertilizer, animal food and a host of other useful products.

"On top of this, the system is basically energy free, powered almost completely by sunlight, wave energy and forward osmosis," Trent said.

He admitted that there are a lot of challenges to overcome to turn the OMEGA concept into a reality.

"There's biology — what strains of algae are best at producing oil, and can we make them grow in the system? There's engineering — not just plastic bags in the ocean, but the whole system design and all of the logistics involved in maintaining such a system. There's the economic angle — OMEGA will require new infrastructure. And of course there are the environmental issues, including policies, politics and public acceptance."

Despite the magnitude of the undertaking, Trent was adamant about the need to push ahead. "It's clear that something has to be done and done soon about our energy problems. Things are not sustainable the way they are now.

"OMEGA may not be the best way to go, but we need to investigate it to determine its technical and economic feasibility. We need to try other new ideas as well. If we wait too long, the environment will be the first thing to go as we do whatever it takes just to feed the growing population."

Google provided initial seed funding for the Algae OMEGA project. It is currently funded by NASA and the California Energy Commission's Public Interest Energy Research (PIER) Program.

"This challenge is too big for any one agency. It isn't easy but I believe it is doable.

"After all, we put men on the moon and brought them home alive. We're building the International Space Station and planning expeditions to Mars. We've built oil platforms that can withstand North Sea winter storms and constructed huge islands off the coast of Dubai. We can certainly put algae in bags in the ocean to make oil in a way that helps solve the world's energy and environment problems. The question is whether we are sufficiently motivated."

Readers interested in learning more about the OMEGA project or who have ideas that could potentially contribute to the project can contact modlin2 [at] llnl.gov (Doug Modlin), chief engineer in Global Security's S Program.