Study confirms age of oldest fossil human footprints in North America

(Download Image)

(Download Image)

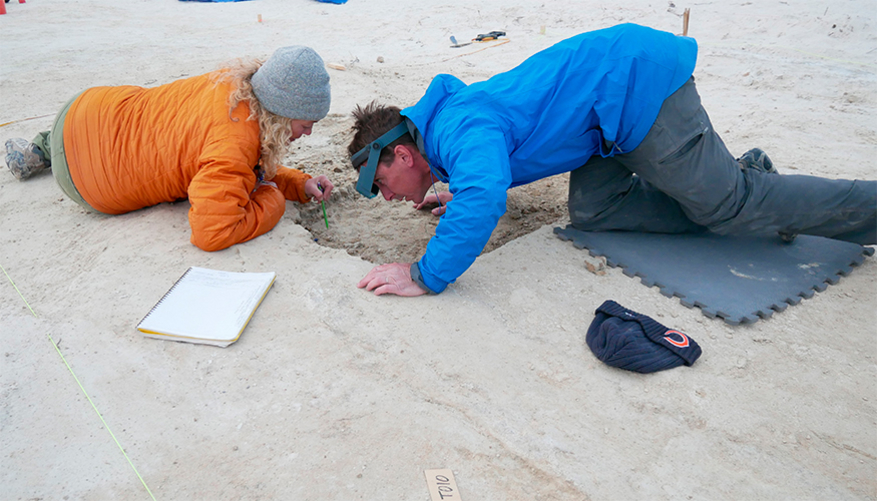

New research reaffirms that ancient human footprints found in White Sands National Park, New Mexico, date to between 21,000 and 23,000 years ago, placing humans in North America thousands of years earlier than once thought. Image courtesy of USGS.

New research reaffirms that human footprints found in White Sands National Park, New Mexico, date to the Last Glacial Maximum, placing humans in North America thousands of years earlier than once thought.

In September 2021, U.S. Geological Survey researchers and an international team of scientists announced that ancient human footprints discovered in White Sands National Park were between 21,000 and 23,000 years old. This discovery pushed the known date of human presence in North America (originally thought to be about 14,000 years ago) back by thousands of years and implied that early inhabitants and megafauna co-existed for several millennia before the terminal Pleistocene extinction event.

“The immediate reaction in some circles of the archaeological community was that the accuracy of our dating was insufficient to make the extraordinary claim that humans were present in North America during the Last Glacial Maximum. But our targeted methodology in this current research really paid off,” said Jeff Pigati, USGS research geologist and co-lead author, with USGS geologist Kathleen Springer, of a newly published study that confirms the age of the White Sands footprints.

The Last Glacial Maximum, from about 26,500 to 19,000 years ago, was the most recent time that ice sheets were at their greatest extent. Ice sheets covered much of northern North America, northern Europe and northern Siberia, causing sea level to drop by 120 meters and profoundly affecting Earth's climate.

Human footprints at White Sands National Park were reported to date to between ~23,000 and 21,000 years ago based on radiocarbon dating (14C) of seeds from the aquatic plant Ruppia cirrhosa, found in the fossilized footprints. But aquatic plants can acquire carbon from dissolved carbon atoms in the water rather than ambient air, which can potentially cause the measured ages to be too old.

In a new follow-up study, published today in Science, researchers, including Susan Zimmerman of Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL’s) Center for Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (CAMS), used two new independent approaches to date the footprints, both of which resulted in the same age range as the original estimate.

“This study really shows the power of using multiple chronometers together – each technique has its own strengths and weaknesses and uncertainties, and the agreement between them makes the result much more robust than any one technique alone,” Zimmerman said.

The team used new 14C ages of terrestrial pollen collected from the same stratigraphic horizons as the Ruppia seeds, along with optically stimulated luminescence ages of sediments from within the human footprint-bearing sequence, to evaluate the accuracy of the seed ages.

In the new study, researchers focused on radiocarbon dating of conifer pollen, because it comes from terrestrial plants and therefore avoids potential issues that arise when dating aquatic plants like Ruppia. The researchers used physical and chemical procedures to separate and concentrate the pollen preserved in the sediments, and then approximately 75,000 pollen grains for each sample were isolated using flow cytometry at Indiana University. The pollen radiocarbon dating was then performed at CAMS. The pollen samples were collected from the same layers as the original seeds, so a direct comparison could be made. In each case, the pollen age was statistically identical to the corresponding seed age.

The radiocarbon dating of pollen separated from sediment was actually pioneered by CAMS scientist Tom Brown in a 1989 paper from his dissertation work and “combined with flow cytometry has become the critical technique that will allow high-resolution chronologies for many records of past climate, volcanism and other Earth processes of immediate importance to society, in lake sediments where plant and charcoal material for 14C dating are simply not preserved,” Zimmerman said.

“Pollen samples also helped us understand the broader environmental context at the time the footprints were made,” said David Wahl, USGS research geographer and a co-author on the current Science article. “The pollen in the samples came from plants typically found in cold and wet glacial conditions, in stark contrast with pollen from the modern playa which reflects the desert vegetation found there today.”

In addition to the pollen samples, the team used a different type of dating called optically stimulated luminescence, which dates the last time quartz grains were exposed to sunlight. Using this method, they found that quartz samples collected within the footprint-bearing layers had a minimum age of ~21,500 years, providing further support to the radiocarbon results. With three separate lines of evidence pointing to the same approximate age, it is highly unlikely that they are all incorrect or biased and, taken together, they provide strong support for the 21,000 to 23,000-year age range for the footprints.

The research team included scientists from the USGS, LLNL, the National Park Service and academic institutions. Their continued studies at White Sands focus on the environmental conditions that allowed people to thrive in southern New Mexico during the Last Glacial Maximum and are supported by the USGS-NPS Natural Resources Protection Program and the USGS’s Climate and Land Use Change Research and Development Program.

Contact

Anne M. Stark

Anne M. Stark

[email protected]

(925) 422-9799

Related Links

U.S. Geological SurveyWhite Sands National Park

Science

Tags

Earth and Atmospheric ScienceAtmospheric, Earth, and Energy

Center for Accelerator Mass Spectrometry

Physical and Life Sciences

Science

Featured Articles