New film captures LLNL engineer-turned-astronaut’s inspiring journey

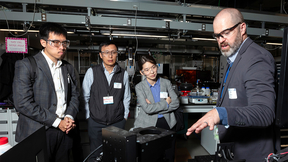

José Hernández tours the National Ignition Facility with another former astronaut, Jeff Wisoff, who is the principal associate director of NIF & Photon Science. (Photo: Carrie Martin/LLNL)

It was a chilly December night in 1972. Under a tawny half-moon hovering over California’s Central Valley, an impressionable 10-year-old boy named José Hernández looked skyward and saw his future.

Hernández had spent that evening with his family as they gathered around their black-and-white television. Young José, a fan of "Star Trek," performed his usual duties as his father’s remote control and human antenna. But this night was special. As Hernández, rabbit ears in hand, contorted himself to provide the best quality picture he could muster, he watched, upside-down, the grainy images of NASA astronaut Gene Cernan walking on the moon, the last human to do so. As newsman Walter Cronkite narrated the scene, Hernández gazed at the snowy screen, transfixed, feeling as if the signal coursing through his body was somehow programming his destiny.

“I stayed there for a good 20 minutes until my family had their fill, and they finally allowed me to let go of the antenna,” Hernández recalled. “Then I was sitting in front of the TV with a fuzzy picture, and I’m going in and out of the house, looking outside and seeing the moon and coming back inside and hearing [Cernan] talk to Mission Control. I was in awe. I thought, that’s what I want to be. I want to be him. I want to be an astronaut. That’s how the dream was conceived.”

The moment proved to be more than just a flight of fancy — it started a trajectory that would take him from his family’s two-bedroom dilapidated rental in Stockton to Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, to the zero-gravity of near-Earth orbit, to the White House, and most recently, to the vineyards near Lodi, where he and his father Salvador grow grapes to create their own wines.

Now, Hernández ’s inspiring journey from the fields to the stars will have a worldwide audience, as Amazon Studios brings his life story to the small screen with the new film “A Million Miles Away.” Based on Hernández ’s autobiography “Reaching for the Stars: The Inspiring Story of a Migrant Farmworker Turned Astronaut,” the film will begin streaming on Sept. 15, coinciding with the start of Hispanic Heritage Month.

Hernández, who worked closely with the production team and got an advanced screening of the movie in Los Angeles with his daughter (and social media influencer) Vanessa, said he was impressed with the film and its positive message, which he hopes “serves as a beacon” for anyone who dares to follow their hearts.

“It's kind of surreal,” Hernández said of seeing his life portrayed in film. “I never grew up and said, ‘Gee, I hope I grow up and they make a movie about me;’ that's just not one of the goals in life I had,” Hernández said. “It's incredibly humbling to have a movie done about yourself, but I embrace it from the perspective that I hope it helps provide direction for kids and adults that anything is possible in life. What I want people to take away from the movie is: Don't be afraid to dream big; if you're willing to put the time and effort in and make the commitment to yourself to try and reach that dream, make it into reality.”

It’s a message Hernández has spread through his hundreds of motivational speaking engagements over the years, talking to educators, industry and students all across the country, and encouraging them to set ambitious goals. Through the reach only possible through film, he feels the message could resonate more broadly for generations to come.

“If you have a goal and draw yourself a roadmap, and you're willing to prepare yourself and make sacrifices, good things will come — that's what we've been preaching all the time when I give my talks, and I'm so glad to get put into a movie because this is a way of reaching millions of people in a short period of time,” Hernández said. “Hopefully, it becomes a classic that's watched over and over, and as kids grow up, they see it and get inspired. I’m very, very excited about it.”

Hernández walks the walk. The son of migrant farmworkers, he grew up toiling in the fields, picking grapes, cherries or whatever produce was in season. His youth was spent following the harvest, journeying back and forth between California and Mexico. Born in French Camp, California, Hernández relocated with his family every few months, finally settling in Stockton at the urging of his second-grade teacher. Hernández didn’t learn English until he was 12, but he excelled at math and was determined the rest of his life would not be spent with his hands and knees in the soil.

“Even though my parents only had a third-grade elementary school education, they believed in education; they didn’t want us to follow their lifestyle,” Hernández said. “They would point to a bank manager wearing a suit and working in an air-conditioned building and say, ‘You want to be like him, not like us.’ And school was the key. I credit my parents with putting those values and expectations that college was what we had to do.”

Rather than steer him away from his out-of-this-world ambitions, Hernández’s father empowered him with a five-ingredient “recipe”: decide what you want to be (which José had already done), realize how far you need to go, draw yourself a roadmap, get a good education and always do more than what people expect. Hernández took the work ethic he had cultivated in the fields and poured it into his schooling, beginning a path to becoming an engineer as his older brother Salvador had done. Working at restaurants and canneries to pay his tuition, Hernández attended the University of Pacific and earned a degree in electrical engineering and later, a master’s from the University of California (UC), Santa Barbara.

First introduced to LLNL on a visit to the Discovery Center in elementary school, Hernández joined the Lab as an intern in 1984. With his astronaut dream firmly rooted, Hernández looked for opportunities to add skills to his resume that would get him closer to fulfilling his destiny. He worked on an X-ray laser that would be deployed to space, part of the “Star Wars” Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) program. Then, he tackled a project to build the first digital mammography system for early detection of breast cancer. He became a group leader in Chemistry and Materials Science and served as president of Los Amigos Unidos, the Lab’s Hispanic activities club. When he had the opportunity to go to Russia as part of the Highly Enriched Uranium (HEU) purchase agreement, he jumped at it, and began learning to speak Russian, knowing that future NASA missions would require Russian collaboration.

In 1992, Hernández applied to become a NASA astronaut, the first of what would be many unsuccessful attempts. He framed his initial rejection letter as motivation, but after the sixth, he crumpled it up and angrily threw it on the floor, convinced he was giving up his pursuit for good. Instead of conceding defeat, Hernández began to study the qualifications of previous classes of astronauts. He took flying lessons at the Tracy airport and earned his pilot’s license. He saw most astronauts also had SCUBA training, so he joined the Lab’s Vaqueros del Mar SCUBA club and became a certified diver.

“What kept me going was the fact that everything I was doing was helping my career at the Lab, so I didn’t feel like I was wasting my time,” Hernández said. “I thought, ‘just keep doing what you’re doing, as long as it’s not affecting your career, I’m OK. I’m moving in the right direction.’ I liked the pace I was moving at the Lab career-wise, so I wasn’t stagnating. Everything was working out.”

In 1999, Hernández went to Washington, D.C., on assignment at the Department of Energy headquarters. He joined the Nuclear Material Protection Control and Accountability program, initiated to help the Russians control and protect their nuclear material. Though he continued being snubbed by NASA as an astronaut, the agency offered him a job as an engineer. Sensing his dream about to be realized, Hernández took a pay cut and a leap of faith, relocating to the Johnson Space Center in Houston in 2001. After 11 straight rejections, his tenacity finally paid off. In 2004, at the age of 41, Hernández finally got the call he’d been waiting for: the one welcoming him to the 19th class of NASA astronauts.

“I was so happy,” Hernández said. “I remember when I left, the Lab was kind enough to say, 'we’ll put you on leave without pay and said when you’re done playing, you can come back.'”

LLNL physicist Harry Martz, director of the Lab's Nondestructive Characterization Institute, worked with Hernández applying nondestructive evaluation to materials for the SDI program. Martz has stayed in touch with Hernández over the years, and recalls being impressed with Hernández’s hard work, tenacity and optimistic attitude, even in the face of repeated disappointment.

“Sometimes people say certain things and you think ‘yeah, whatever.’ And when he didn’t make it the first few times you thought, ‘well, it’s probably over, he’s not going to do it.’ But he just had that drive, that perseverance to keep trying and not accept failure,” Martz said. “A lot of people get rejected and they get all depressed, but he looked at it like ‘at least I got a letter from NASA and that’s a start.’ He was very creative to think, ‘what do these other astronauts have that I don’t have, and I have to do these things.’ He put all these things together, so it was hard for NASA to refuse him.”

Up, up and away

Officially an astronaut candidate, it was on to flight school in Florida and then to Houston for two years of basic training. Floating in pools with mockups of the Space Shuttle and sections of the International Space Station, Hernández practiced spacewalks underwater and got accustomed to wearing spacesuits in zero gravity. After earning his wings, he was selected as the flight engineer aboard the Space Shuttle Discovery on a two-week mission to resupply the International Space Station (ISS). Following 18 more months of grueling training, close to midnight on Aug. 28, 2009, Hernández’s lifelong ambition was finally realized, as Discovery launched from Cape Canaveral on a two-week mission.

“You go from zero to 17,500 miles an hour in eight-and-a-half minutes. Once you’re up there 300 miles above the ground, you’re going around the world once every 90 minutes in a continuous fashion, and you’re free-floating in a microgravity environment,” Hernández said. “Once the solid rocket boosters light up, you know you’re going somewhere because you can’t turn them off.”

During the mission, an international collaboration involving astronauts from five other countries, Hernández assisted on spacewalks and ISS repairs, operating the shuttle’s robotic arm, installing equipment and experiment modules, and helping dock and undock the shuttle from the space station. He also happened to be the first astronaut to bring an Oakland Raiders flag to space. One of the first things he did in orbit was to view the planet from a perspective only about 550 humans have ever had. The experience permanently altered him.

“When you see it, it boggles your mind,” Hernández said. “I couldn’t make out where Canada ended and the U.S. began, or where the U.S. ended, and Mexico began. I thought, ‘I had to come here to realize that down there, we’re really just one — that borders are human-made concepts designed to separate us.’ I wish we could have our world leaders experience this a-ha moment like I had, because I guarantee you if we did that, our world would be a much better place than it is today.”

His second takeaway came during one of the shuttle’s 219 revolutions around the Earth, as it passed from the dark side of the planet into the light of sunrise.

“When the sun hits the horizon at the right angle you can see the thickness of our atmosphere, and you realize how scary-thin and fragile our environment is — that’s when I became an instant environmentalist. I said, ‘Man, they’re right. This looks like a very delicate balance, and anything we do down there is going to affect the balance.’ I can see where we can get to a point where it’s a runaway problem and we won’t be able to control it, and suddenly we’ve got an imbalance that can affect our climate and environment. I think we’re seeing some of that already, and that’s what really woke me up.”

After 14 days in space, Hernández returned home, exhilarated and humbled by the experience. NASA had announced the end of the Space Shuttle program, and Hernández knew if he were to go back to space, it would come at a high cost. It would have to be aboard a Russian Soyuz rocket, requiring four more years away from his family, much of it in Russia. With five children, Hernández felt it was time to move on to other endeavors.

Back on terra firma, but reaching for the stars

Like most returned astronauts, Hernández was given his pick of desk jobs at NASA, deciding on the agency’s Office of Legislative and Intergovernmental Affairs. He was invited to a Cinco de Mayo event at the White House, where he met President Barack Obama in a photo-op lineup. Upon discovering Hernández was an astronaut, Obama asked him if he’d ever thought about running for Congress. Hernández was taken aback; the thought hadn’t crossed his mind before.

Not long afterward, Hernández was invited to Texas for a talk by Obama on immigration reform. Near the end, the president gave attendees a microcapsule of Hernández’s life story. Again, Obama asked Hernández if he’d thought about running. Realizing Obama was serious, Hernández said he’d talk about it with his family. When Hernández received the Medallion of Excellence for Leadership and Community Service from the Congressional Hispanic Caucus Institute in Washington six months later, Obama was in attendance. Following the presentation, Hernández was escorted to the front of line for picture with Obama and his wife Michelle.

“It was this third time that he finally said, ‘I’m going to stop playing around, I’m going to do the ask: will you run for Congress?” Hernández recalled. “At that point I figured that’s more of an order than a request. I thought it was my duty to salute the flag and I said ‘yes, sir.’”

With the end of the space shuttle program, combined with the pressure to run for office, Hernández decided to leave NASA and begin a congressional campaign for the 2012 election. His only prior political experience was as student-body president in high school, but Hernández felt he had a natural knack for politics. The downside was he couldn’t run in his home district, which was already governed by an incumbent Democrat. He was moved over to California’s 10th Congressional District, where he was pitted against the Republican favorite, Jeff Denham. Hernández lost by a slim margin.

“We did make some inroads, but it was a tough race,” Hernández said. “Unfortunately, the cards weren’t on the table, but losing the election was the best thing that could’ve happened, because I don’t think I would’ve been able to get my kids through college on a Congressman’s salary.”

It also freed up Hernández to become a consultant in aerospace and renewable energy, a job that took him around the world. He worked as technical advisor for the Mexican government, which sought his help in selecting launch providers for three Boeing built satellites. The three-and-a-half-year, $1.2 billion project saw him travel to French Guyana, Kazakhstan and Florida to assist with rocket launches. He continues to consult with universities, including a college in Mexico where he helped create an aerospace engineering program. In doing so, he helped a university design, build and — with the help of NASA — launch a CubeSat miniature satellite into space. It marked the first time a university in Mexico had successfully operated a CubeSat in Earth’s orbit.

Along with Hernández’s seat in the exclusive club of NASA astronauts came the inevitable fame, from throwing the first pitch at an Oakland A’s game to appearing in a commercial for Modelo beer with his father. Though Hernández’s journey took him far from the rural fields he grew up in, he’s never forgotten his roots, capitalizing on his notoriety to influence a younger generation of students from underprivileged backgrounds particularly in his hometown of Stockton, where he regularly engages in community events and STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) outreach.

“Mr. Hernández is an example of what I strongly believe, talent is universal, but opportunities are not,” said former Stockton mayor Michael Tubbs. “Our communities have an ambulance of smart, talented and resourceful individuals, that just need an opportunity to succeed in life. Mr. Hernández started from humble beginnings and now he has reached the stars. He is an example for all of our youth that with hard work, you can become anything you want to be.”

Sparked by the excitement he saw generated at home after his selection, he founded the Reaching for the Stars Foundation (Astrojh.org) in 2006 to motivate children in the Central Valley to pursue STEM-related careers. Once a year, more than 1,200 fifth graders are provided with a single-day, hands-on science class. Middle and high school students can take a five-week summer academy at the University of the Pacific to expose them to college math and science curricula. The foundation also awards scholarships to graduating seniors. Motivational speaking, Hernández said, came to him quite by accident.

“When I came home, I saw the impact I had on the community and especially the kids,” Hernández said. “I immediately recognized that I was a role model, whether I wanted to be or not. It seemed like I had lightning in a bottle; people were actually listening. It kind of happened without me wanting it to, but it’s seemed to work out pretty well.”

Hernández passed on his passion for education to his five children. Vanessa graduated from Loyola Marymount with a degree in business management and works for a cosmetic company, in addition to cultivating her sizable social media presence. Another daughter, Marisol, earned her degree in actuary sciences from UC Santa Barbara. His oldest son Julio, who spent two summers working at the National Ignition Facility, recently obtained a Ph.D. in aerospace engineering from Purdue University and has applied for jobs at LLNL. His youngest son Antonio is starting his third year in mechanical engineering at UC Merced. Daughter Karina has special needs and attends an adult transition school.

Like a true Renaissance man, during the COVID-19 pandemic, Hernández got into winemaking. He purchased a vineyard near Lodi and the winery that bought his grapes invited him on a tour on their winemaking facility, where he got hooked on the process.

“I went to the facility and told myself ‘Yeah, this isn't rocket science, and even if it was, I got that covered anyway,” Hernández joked. “So, I started dabbling; I took a few courses at UC Davis, and then before I knew it, after a couple of years, I came up with some concoctions that I liked.”

With his father running the vineyard’s operations, Hernández began making his own wines working with a “crush-to-bottle” service and turning the venture into an online wine shop called Tierra Luna Cellars. Hernández picks the grapes, and he and his father make the wine and bottle it for distribution. They also have a storage facility and a fulfillment center to handle online orders.

“There's an old saying, ‘You can take the kid out of the farm but not the farm out of the kid.’ That’s pretty much true for me because I love being in the outdoors, and I love working the land. When I got this opportunity to buy this vineyard, I jumped at it. And not being one that just sits down and rests on my laurels. I said, ‘What's the next logical step in this adventure of owning a vineyard? Hey, why don't I make my own wine?’ So, Cellars was born.”

Hernández has produced his own Sauvignon Blanc and Zinfandel varietals and a blend with grapes purchased from the Napa area, with each wine predictably carrying a name related to astronomy. While the winery is virtual for now, Hernández wants to build a tasting room and the infrastructure for his own brick-and-mortar winemaking facility.

With all he’s accomplished, Hernández said he still considers himself a “Labbie” at heart, and his connection to LLNL remains strong. Besides staying in touch with former co-workers and friends he made through Los Amigos Unidos, his nephew, Gabriel Corona, currently works at the Lab as an engineer in the Lab’s Life Extension Program.

In Aug. 2021, California Governor Gavin Newsom appointed Hernández to the University of California (UC) Board of Regents, where his responsibilities include representing UC on the Lawrence Livermore National Security Board of Governors and providing oversight for the Lab. Hernández will meet at least twice a year with the Lab director for an overview of the Lab’s programs and budget. The role allows him to maintain direct ties to the Lab that he called home for 15 years — a place he credits with providing the experience he needed to achieve his goals and the opportunity to perform his most impactful work.

"I look at working at the Lab as one of the highlights of my career,” he said. “If I look back at everything I’ve done, people probably think I’m most proud of being an astronaut and going to space, but quite the contrary. What I’m most proud of is the fact that the Lab embraced the digital mammography project, the work Clint Logan, Laura Mascio and I did, allowed us to assist a private company to make a product that was better than what was available at the time. I look back and know that project has saved lives. That is what makes me most proud.”

Contact

Jeremy Thomas

Jeremy Thomas

[email protected]

(925) 422-5539

Tags

CareersEngineering

Featured Articles