Lab’s first responders recall shock, triumph and tragedy in Sept. 11 aftermath

(Download Image)

(Download Image)

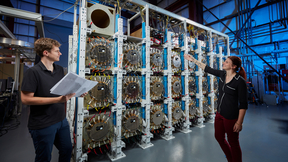

A joint team of LLNL and New York City Fire Department firefighters search the surface of the rubble pile at the World Trade Center site for potential voids. Photo by John Chang/LLNL.

Editor's note: The following is part of a series of articles looking back at the Lab's response immediately following the Sept. 11 attacks and our contributions since that day 20 years ago.

Wayne Shotts was asleep when the phone rang on the morning of Sept. 11, 2001. His wife Jacki picked it up. It was their son, Ken. He sounded panicked.

“Where’s dad?” Ken asked.

Shotts, a frequent flyer as LLNL’s deputy director for Operations and head of the Lab’s Nonproliferation, Arms Control and International Security (NAI) division, was home safe. He turned on the TV, watching in horror as United Flight 175 slammed into the south tower of the World Trade Center.

“Words just can’t describe it,” Shotts said. “It was such a startling thing to see. Immediately your mind starts reeling: ‘Who’s done this? What can be done to help? How do we respond to this?’”

Throughout a nearly 30-year career in national and global security, Shotts had prepared for the unexpected, but he’d never imagined an attack of this scale using aircraft. He dressed quickly, and by the time he arrived at the Lab, the Emergency Operations Center had been activated. Shotts began working with then-Deputy Director for Science & Technology Jeff Wadsworth (filling in for Lab Director Bruce Tarter, who was at a conference in Japan) to assess the situation.

Within minutes of the attacks on the Twin Towers and the Pentagon, the Lab’s intelligence programs went to work monitoring traffic for additional terrorist threats. Requests started pouring in for experts in nuclear, chemical and biological counterproliferation, along with calls for technologies that could aid search and recovery efforts. In his acting role, Wadsworth determined NAI would handle the emergency response and deployment efforts.

“The Lab was abuzz with activity trying to figure out what was happening,” Shotts recalled. “We were just responding to one thing after another. The place was totally focused on what we had to do.”

It wouldn’t be long before LLNL was called upon to send its resources and people to the ruins of the World Trade Center.

Searching for signs of life amid the rubble

An “aspiring engineer” at LLNL, John Chang awoke to news of the attacks on the radio. Chang, who also volunteered in search and rescue with the San Mateo County Sheriff’s Office’s Bay Area Mountain Rescue Unit, had been working on Microwave Impulse Radar (MIR) technology, which had applications in remote health monitoring and combat casualty care.

Prior to 9/11, Chang’s team had evaluated the low-power, portable MIR device — roughly the size and appearance of a handheld lantern flashlight — for remote sensing of vital signs such as heartbeat and breathing. MIR’s portability and capability made it an intriguing possibility for emergency disaster response, and preliminary tests were promising.

Serendipitously, an Air Force general had recently visited the Lab and was briefed on the technology. Word got to the Department of Energy, and on Sept. 12, the office of then-Energy Secretary Spencer Abraham called to see if MIR could be used to search for survivors trapped under the World Trade Center rubble.

“At the very least, we (thought we) could offer up a technology that hasn't been around and isn't necessarily widely known, and certainly not something that one can buy off-the-shelf,” Chang said. “It was in the research and development stage, but to be able to support as needed, we offered it.”

A team of 10 LLNL employees was hastily assembled, and the equipment pared down to the essentials. The next day, with air traffic shut down nationwide, the team boarded Sec. Abraham’s government aircraft and departed Stockton for New York City. Arriving in Manhattan in the middle of the night, the pilot flew over the still-smoldering Ground Zero. The view was sobering.

“When we did the fly-by and saw the big plume of smoke that was still coming out, it was very surreal,” said safety engineer Dann Haynes, a member of LLNL’s Hazards Control team. “I'd been to a lot of natural disaster responses and a few bombings, and none of them captured the sheer destructiveness and devastation we saw there.”

On Sept. 15, the MIR team entered the inner perimeter of the debris field. Working up to 16 hours a day alongside national guardsmen, off-duty firefighters and the Massachusetts Task Force 1 Urban Search and Rescue team, they deployed the technology and showed the rescue crews what MIR could do.

“The days were long,” said LLNL engineer Doug Poland. “We went to some of the edges of the pile and ran the equipment through its paces and showed (the Massachusetts team) the motion detection. Things worked pretty well; that certainly helped us in terms of credibility and helped their understanding of what MIR might bring to the effort.”

As the days passed, it became clear the odds of finding any survivors under the rubble were extremely remote. The team soon shifted to using the prototype MIR devices to provide accountability for search and rescue crews in the event they themselves became trapped or injured.

“We had this incredible devastation and all the stress and emotion of all those first responders that were part of the search,” said Haynes, who worked with outside agencies to evaluate the debris pile for hazards. “A lot of times they weren't just looking for strangers on the collapsed building —they were looking for family and coworkers.”

The team offered helping hands in other ways. While Chang was on a search assignment with a NYFD search team, he joined a human chain of rescuers, covering a distance about the length of a city block. Balancing on the still-unstable rubble, Chang helped pass rescue and shoring equipment and body bags in five-gallon buckets to the center of the debris field as firefighters attempted to retrieve the bodies of their colleagues. In the opposite direction, the bucket brigade passed back recovered remains for transportation to the morgue.

The team left Ground Zero on Sept. 19, and although they were unable to find any survivors, team members said the work helped “put LLNL on the map” as an institution that could combine technical expertise, operational readiness and threat awareness to meet some of the most nation’s most urgent needs.

“We were there for only a relatively short (time), but it was high-octane; it was a really intense engagement,” Chang said. “We had a motley crew of Livermore responders. It could have been really bad, because many of us never worked together before we got put into this environment with such intensity. But instead of fragmenting, we really forged together.”

Sifting through reports for possible threats

Part of the Lab’s Counterterrorism and Incident Response Division, LLNL’s Nuclear Assessment Program (NAP) — headed by LLNL veteran Fred Jessen and his deputy Rob Allen — had spent decades looking for signs that terrorist groups might try to acquire and use a nuclear device.

Within minutes of hearing of the World Trade Center attack, Jessen, Allen and other NAP personnel activated NAP’s Threat Assessment Center (TAC) and began looking into potential nuclear threats, while other Lab personnel sifted through intelligence reports for hints of follow-on nuclear, biological or chemical attacks.

The sheer volume of incoming traffic forced the dozen-member NAP team to split into two shifts, operating 24 hours a day, seven days a week for the next three months, assessing nuclear-related threats and advising federal officials on appropriate responses.

“It was just a flurry of activity,” Allen said. “We knew we had to turn all our resources on and start preparing to respond and provide the kind of information that decision-makers throughout the government needed.”

Katie Adams, a member of NAP’s analyst support team, was in Albuquerque when the attacks occurred. She drove her rental car back to California during the air travel shutdown, arriving at the Lab on Sept. 15. She spent her 12-hour shifts searching through reports and international media and relaying relevant information to Lab analysts.

“It was constant,” Adams said. “We were all in that mind frame of this horrible attack and we didn't want to miss anything. So, we were just go, go, go.”

On 9/11, Susan Allen, a molecular biologist and intelligence analyst in LLNL’s Z Division — the intelligence arm of the Lab — was giving a briefing in downtown Washington, D.C. when word came that a plane had struck one of the Twin Towers. After watching the second airliner impact the south tower on TV, Allen drove with a colleague to Pentagon City. She passed by the Pentagon, where she could see the gaping hole caused by the crashed American Airlines flight 77.

“The crews were there working, and they had hung the American flag off the side of the Pentagon by that point,” Allen recalled. “I just stopped where I was on the highway, I pulled over and looked at the damage, and it was shocking. It was almost too much to take in seeing it in person. It was almost overwhelming.”

Allen flew home on Sept. 18. Back at the Lab, she began looking into al-Qaeda and the possibility of a bio-terror attack. After working with Z Division’s Bio team for several weeks, she was assigned to Washington to support the U.S. intelligence community.

The day Allen arrived, news of the “Amerithrax” case broke with the first reported death from anthrax-laced letters sent to elected officials and prominent members of the media following Sept. 11. Allen spent the next several weeks working 15-hour days to determine the source of the letters, advising the government and inspecting facilities and mail-handling operations. She stayed in contact with her colleagues at LLNL and at other laboratories, including scientists that were analyzing the anthrax samples.

“You worked as hard as you could all day and into the evening, and then went to the hotel and crashed and got up again the next day and did it all over again,” Allen said. “It was satisfying in the sense that you felt like you were doing something of value and having the impact for your country. I was very proud to represent the Lab and bring our expertise into the discussion and be a player.”

The NAP team provided dozens of terror assessments for the intelligence community in the weeks after Sept. 11, exceeding its entire workload from the previous year. In the winter, the center scaled back to 12-hour days, remaining in that posture for six more months.

“You felt after 9/11 it really came to a head, but even before that, working for NAI you felt like you were really making a contribution to the country,” said Adams, who retired in 2019. “Even though we were a small program, and most people didn't know we were there, we were searching every single day, all day long, for anything that might be of interest in the course of the analysis. It was the most amazing group I've ever worked with.”

An eye in the sky for search and rescue teams

Mike Carter, an associate program leader under NAI, was sitting on the tarmac at San Francisco International Airport on Sept. 11, waiting to take off for Washington, DC.’s Dulles International Airport when a vague announcement came over the intercom. There had been an accident, and there would be a slight delay until air traffic controllers knew more.

A fellow passenger was on the phone with his daughter in New York City and held it up so Carter could hear. It became clear what was happening was no accident. Flight attendants evacuated the plane, and Carter headed back to the Lab.

“It was the strangest day ever,” Carter said. “Like all Lab employees, I thought, ‘what could the Lab do to help?’”

Within days, a call came from DOE: Could the Hyperspectral Infrared Imaging Spectrometer (HIRIS) system — a technology Carter had helped develop to detect and map gaseous emissions — monitor the air at the World Trade Center site? Efforts had shifted to a cleanup and recovery operation, and officials were concerned over toxic gases and other hazardous emissions coming from the rubble pile that could affect the crews.

“It was a very emotional time for all of us,” Carter said. “The act of helping basically broke us out of the thought of ‘Wow, this has happened to us,’ to ‘We can actually do something that might help this workforce.’ It was a real ‘aha’ moment that this technology that we had pioneered at the Lab could actually be put to something we hadn’t thought of before.”

Carter and his team hastily reassembled the HIRIS instrument and installed it in an aircraft at the Nevada National Security Site’s Remote Sensing Lab. They flew to Teterboro Airport, 12 miles from Manhattan, where they set up a makeshift staging area. To show them what they were up against, NYPD police officers took Carter and lead aircraft operator Brett Wayne through Ground Zero.

“You realize you’re at a mass gravesite,” Carter said. “There are artifacts everywhere; business cards, half-burned letters with somebody’s signature on it. I saw a single red high-heeled shoe. These things just stick with you … I walked out after a couple of hours on the pile with this resolve that we were going to do something to help and that we were there for a reason.”

Several times a day for the next week and a half, Carter’s team flew the HIRIS system around the site. After each flight, they offloaded the data and analyzed it, looking for signatures of deadly phosphene gas, which officials feared could be produced by burning refrigerant tanks, as well as toxic particulates and methane gas. While HIRIS worked as intended, the team didn’t find any hazardous emissions or fires in the leaking tanks: welcome news for disaster recovery crews.

“In the end, we didn’t see anything actionable, but we did everything we could,” Carter recalled. “That's why we show up at work on Monday morning, with the determination that the things we're working on are going to have applications in the real world to make our country safe. Even though we didn't have an impact on the operations at Ground Zero, we could have if we had seen some of the things that we were looking for.”

20 years later, 9/11 leaves a lasting impact

LLNL’s response to the Sept. 11 attacks involved more than 60 employees and helped cement the Lab’s stature as an organization that could apply cutting-edge technologies to unanticipated scenarios and combine technical know-how with intelligence analysis in the interests of counterterrorism and national security.

When the federal government began organizing the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) in 2002, there was brief talk of moving the Lab under the new department. While that didn’t occur, the Lab did form a new Homeland Security Organization to support DHS, appointing Shotts to lead it. Some Lab programs, including NAI, grew rapidly due to increased demand. Many employees involved in the emergency response moved to Washington, D.C. to work in counterterrorism with DHS, the FBI and other agencies.

“9/11 reinforced the notion of how important our planning had been,” said Shotts, who lead NAI until he became deputy director for Operations in 2005. He retired the following year. “Thinking about how nuclear weapons could be used in different ways allowed us to think about the unthinkable. There are few places that have the capabilities and flexibility to work through these scenarios. The Laboratory had a special role to play on 9/11, and I think it still has a special role in counterterrorism.”

For Carter, 9/11 encouraged him to “think more strategically” about how to apply Lab-developed technology. Besides shedding light on what HIRIS could do, Carter’s Ground Zero experience inspired him to explore opportunities in counterterrorism. In 2002, he was part of a group of Lab employees selected to the White House’s Transition Planning Office for the establishment of DHS.

Carter spent the next four years in Washington, serving as deputy director of the Domestic Nuclear Detection Office and director of the DHS Science and Technology Directorate’s Nuclear and Radiological Countermeasures Program. He returned to Livermore in 2006, putting his knowledge of government operations to work on Lab programs.

“I had this wake-up call that there was more that I could do,” Carter said. “We took those initial steps that brought a science and technology foundation to a collection of these 23 organizations across government that didn’t really have an S&T mindset or legacy. That was a really important step in my career, and it all came from the emotional response from being in New York.”

Susan Allen joined Carter on the DHS transition team and, in the years following 9/11, helped the department establish its bio-threat assessment work.

“9/11 really had us engage and bring our technical expertise more readily to the intelligence community and to other government agencies,” Allen said. “It really integrated bringing that deep technical understanding of the intelligence in the context of a real-world threat and understanding how to apply what we got from that technical perspective.”

Just weeks after working with the MIR team at Ground Zero, Chang also responded to the anthrax letter attacks. Twenty years later, Chang considers his role “a gift” that, while traumatic, brought his family closer together and provided him with clarity on how he could best be of service.

“I had to find my own solace, and within my network, a way to understand the experience, but also appreciate it,” Chang said. “It's one of the events that gave me an insight into just how unique not just Livermore is, but how national labs in general bring value to the country. And to be able to do that in a real-time environment was pretty incredible.”

Chang’s teammate Haynes returned to Hazards Control, but because of his 9/11 experience, DHS came calling, and Haynes went on to support some of the agency’s field work.

“It basically changed my entire career path for the better,” Haynes said. “It opened a lot of doors. One of the things it demonstrated to me was that when the rubber meets the road, there is no compromise. Our management was 100 percent behind us, and I consider it to be an incredible honor and privilege that I got to respond.”

After 9/11, Allen became a program leader, managing various response efforts including NAP, NEST and the National Atmospheric Release Advisory Center. After focusing on counterterrorism for years, Allen retired in 2015. He stepped back from the Lab to put more time into his other passion, playing rock 'n roll with his band, and heading the Livermore Live Music organization.

“Sometimes, it's hard to see the forest for the trees of day-to-day bureaucracy, but you know something will happen again; that's the nature of the world. And when it does, the labs will be there, and the people will be there ready to respond,” Allen said. “Now we live in a COVID era, and someday we're going to live in a post-COVID era. Things will always change, but being prepared, having your stuff together and knowing what you're doing will always pay off in the long run.”

Contact

Jeremy Thomas

Jeremy Thomas

[email protected]

(925) 422-5539

Tags

Threat preparednessBiosecurity

Counterterrorism

Featured Articles