LAB REPORT

Science and Technology Making Headlines

Dec. 2, 2016

Glendon Parker, a biochemist with LLNL’s Forensic Science Center, examines a 250-year-old archaeological hair sample that has been analyzed for human identification using protein markers. Photo by Julie Russell/LLNL

The mane ingredient

Using DNA for identification in crime cases often comes with the possibility of contamination in the lab, which unfortunately occurs from time to time when procedures aren’t properly followed. DNA also can get contaminated at the crime scene. But that isn’t the only problem with using DNA to solve crimes. DNA can degrade quickly if exposed to strong sunlight or moist conditions, or there might not be enough DNA to collect.

“DNA is still the gold standard,” says Bradley Hart, who leads the Forensic Science Center at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. “But contrary to what you see on TV, nothing is perfect.”

Hart and his team began their work with hair analysis and believe this new identification method will complement DNA testing within a decade. Early results are promising. “The protein content of hair is variable due to people’s genetic makeup,” Hart explains. There are more than 300 different proteins in hair, although the precise combination differs for each individual. By looking at these proteins, researchers can establish an individual’s protein profile.

And another advantage of hair analysis: Proteins, in hair and elsewhere, are a lot stabler than DNA and can last for a longer time.

Researchers have found that thinning and retreat of the Pine Island Glacier was triggered in the 1940s.

Breaking the ice

Enormous glaciers of West Antarctica appear to be retreating in an “unstoppable” way, according to new research by Lawrence Livermore and collaborators. It’s a process which, if it continues, could ultimately turn the West Antarctic ice sheet into an area of wide open ocean and raise global sea levels by 10 feet.

The new research, led by researchers with the British Antarctic Survey but with accompaniment from scientists at U.S., German, Dutch, Swiss and British universities, focuses on Pine Island Glacier, one of the largest and most threatening in West Antarctica. It is dumping nearly 50 billion tons of ice into the oceans each year -- more than any other glacier on the globe except for its next door neighbor, Thwaites -- and could ultimately raise ocean levels by close to two feet all on its own.

The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry has officially accepted the names for elements 113, 115, 117 and 118.

And the name goes to…

It’s official. The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry has announced the names for elements 113, 115, 117 and 118, in which the latter three Lawrence Livermore and collaborators discovered. They are nihonium, moscovium, tennessine and oganesson, respectively,

The news comes after a five-month consultation process where the public was called to express its opinions on the four proposed names and their corresponding symbols. The symbols for the new elements will be Nh for nihonium, Mc for moscovium, Ts for tennessine and Og for oganesson.

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory and its Russian counterparts took credit for oganesson, named after the famed nuclear scientist Yuri Oganessian.

Scientists may be one step nearer to a solution to the role that clouds play in global warming.

Cloudy outlook on global warming

The implication is that global warming due to rising carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere has been underestimated, according to new research by Lawrence Livermore researchers.

Global air and sea surface temperatures have been carefully observed and recorded for more than a century. But scientific studies of cloud cover -- literally, an overview -- date only from the satellite age.

“Our results indicate that cloud feedback and climate sensitivity calculated from recently observed trends may be underestimated since the warming pattern during this period is so unique,” says Chen Zhou of Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, who led the study.

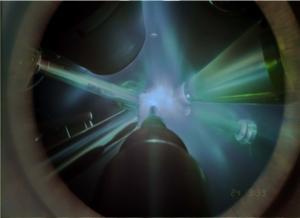

Perovskite is a class of materials to make more efficient and less expensive solar cells.

The power of perovskite

A mineral found in nature may be the key to making more efficient solar panels.

New research by a Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory researcher and collaborators shows that using the mineral perovskite in graded band gap solar cells achieves an average steady efficiency rate of 21.7 percent for all devices.

Unlike the typical silicon-based solar cells, perovskite photovoltaic devices can be made more easily and cheaply than silicon and on a flexible rather than rigid substrate. The first perovskite solar cells could go on the market next year.