LLNL Achieves Fusion Ignition Learn More

LAWRENCE LIVERMORE NATIONAL LABORATORY

Science and Technology

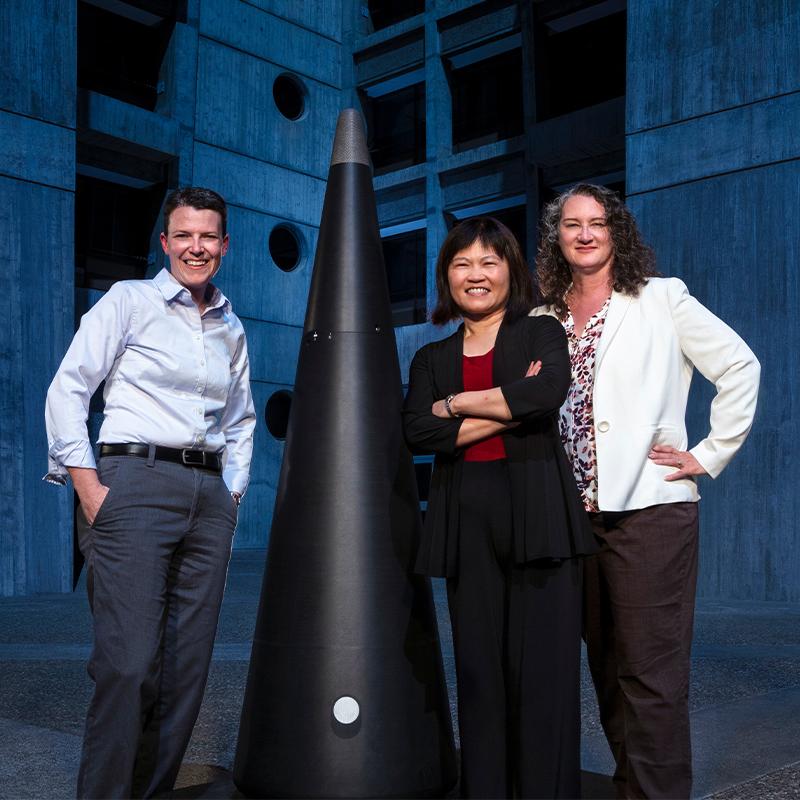

on a Mission

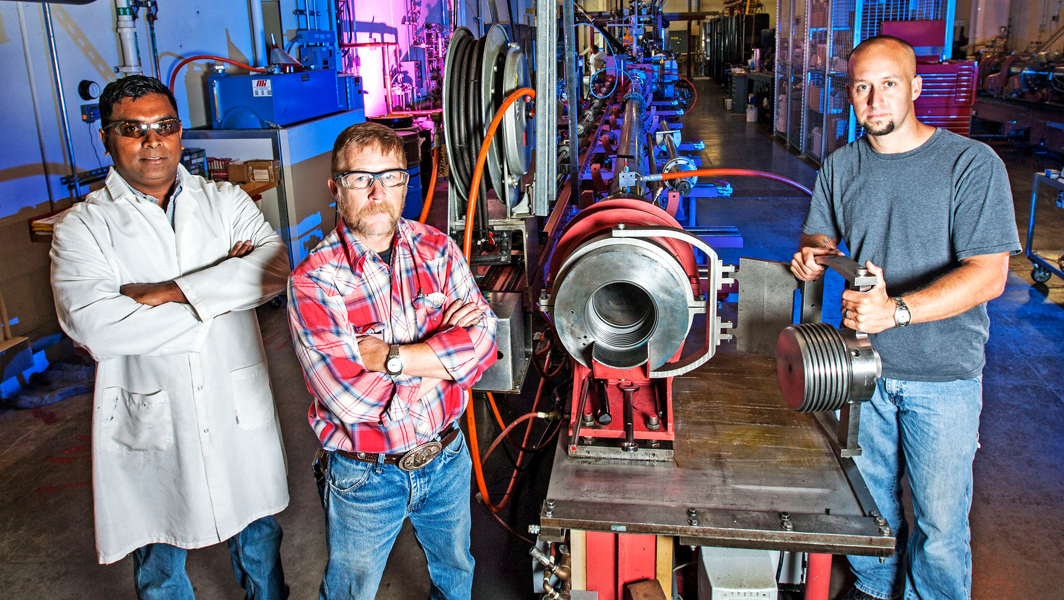

At Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, the realm of what’s possible is only bounded by the questions we’re willing to ask. Our multidisciplinary teams pursue big ideas using innovative science and technology to meet our national security mission and make the world a better place.

Our Mission-Driven Work

For more than 70 years, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory has applied science and technology (S&T) to make the world a safer place. While keeping our crucial mission-driven commitments in mind, we apply cutting-edge science and technology to achieve breakthroughs in nuclear deterrence, counterterrorism and nonproliferation, defense and intelligence and energy and environmental security.

Nuclear Deterrence

We develop and apply the S&T needed to assure the safety, security and reliability of the U.S. nuclear stockpile in an ever-changing threat environment and enable the modernization and transformation of the NNSA production enterprise.

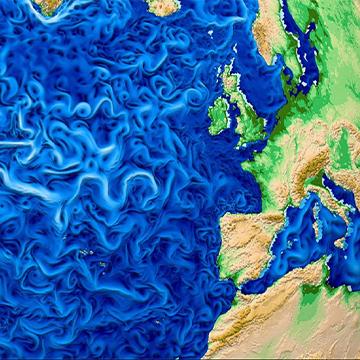

Climate and Energy Security

Our team advances understanding of the global climate system, develops technologies to reduce accumulation of greenhouse gases and pursues the domestic production and supply of affordable clean energy delivered across a secure and sustainable infrastructure.

Threat Preparedness and Response

LLNL provides unique capabilities and innovative solutions to stem proliferation of nuclear, chemical and biological weapons of mass destruction, understand capabilities and anticipate adversarial actions and support response and consequence mitigation of natural and man-made biological threats.

Multi-Domain Deterrence

The Laboratory creates a global strategic advantage through innovative technologies, strategies and analysis to bolster escalation control and defensive capabilities across the full spectrum of domains including strategic defense, conventional strike, space and cyber and technology competition.

Our Latest News

Our Organizations

Each of our organizations provides special expertise required to excel in our national security mission. Bright minds in a variety of fields work together in multidisciplinary teams to address important national issues. At LLNL, everyone contributes to mission success.

Computing

With some of the world’s most powerful supercomputers, complex simulations and leading-edge machine learning, Computing collaborates across the Laboratory and beyond.

Global Security

Global Security’s deep expertise applies to a broad portfolio of national security challenges. From energy security and military technology to weapons of mass destruction and intelligence, the Global Security directorate anticipates, innovates and delivers.

Operations and Business

Operations and Business provides the many services needed to run a large laboratory: Business, Environment, Safety and Health, Human Resources, Infrastructure and Operations, Office of the Chief Financial Officer, Project Management Office and Security Organization.

Strategic Deterrence

Strategic Deterrence strengthens national security through innovations in science and engineering to sustain a safe, secure and effective nuclear deterrent. Pioneering research, engineering and technology are being applied to rebuild and modernize the stockpile.

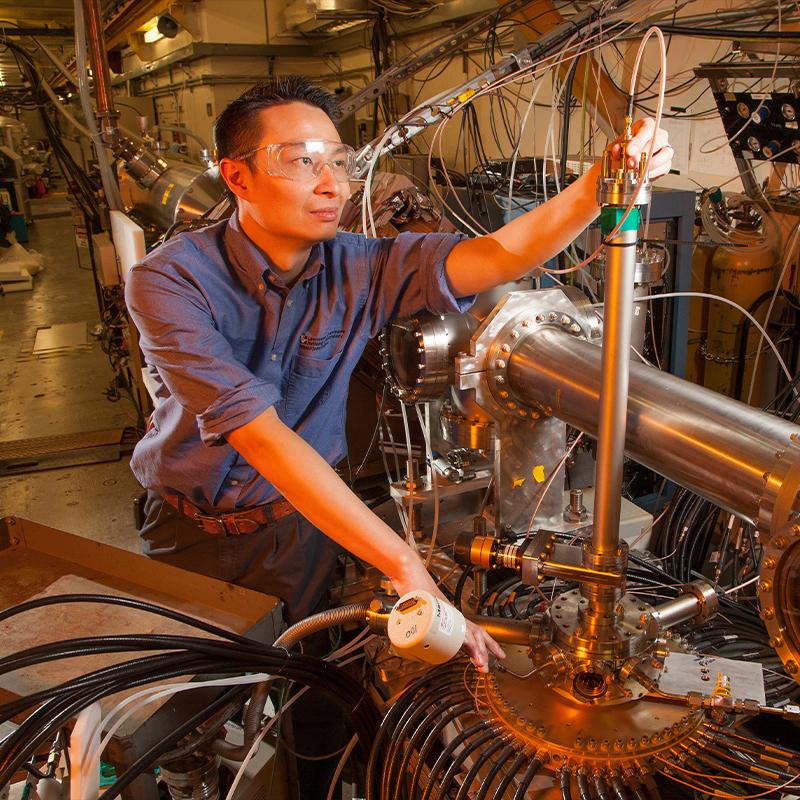

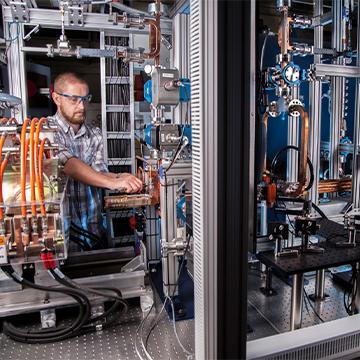

Engineering

The Engineering directorate is a multidisciplinary, collaborative organization focused on achieving scientific and engineering breakthroughs in areas vital to our national security missions — from nuclear security and deterrence to cybersecurity to renewable energy.

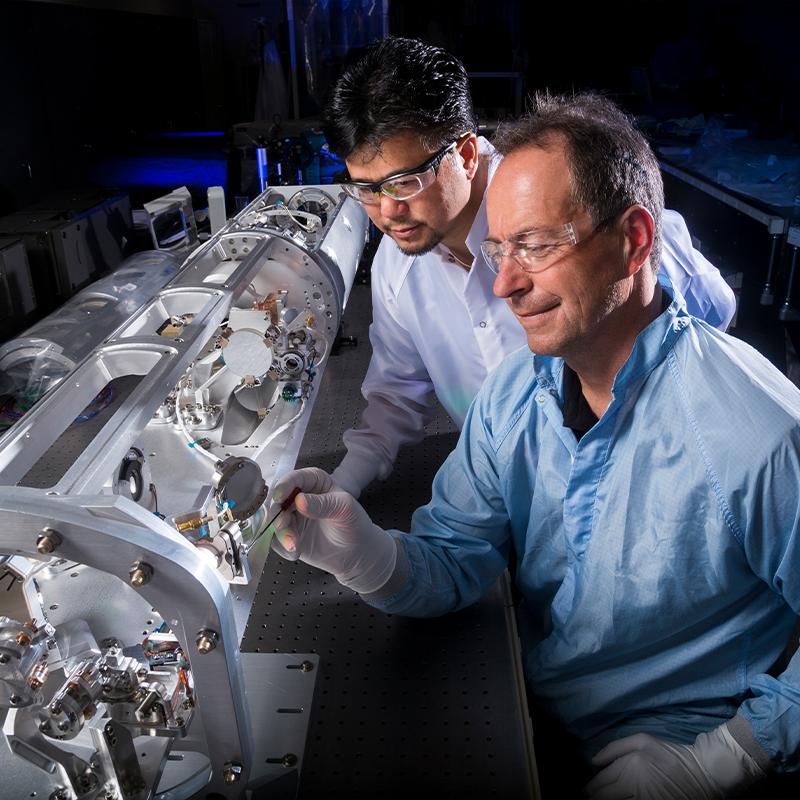

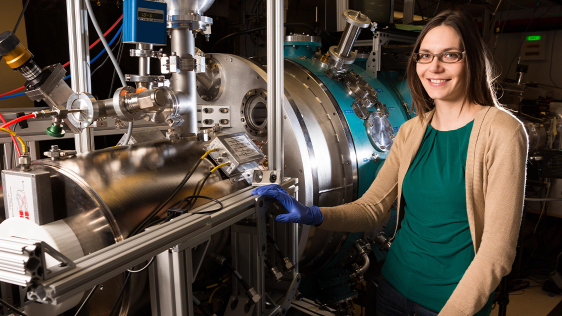

National Ignition Facility and Photon Science

With the world’s largest and highest-energy laser system, NIF and Photon Science spearheads inertial confinement fusion and high energy density science; develops advanced laser, optical, target and diagnostic systems; and applies its capabilities to vital national security solutions.

Physical and Life Sciences

The Physical and Life Sciences (PLS) directorate delivers scientific expertise and solutions to support the Laboratory’s missions. PLS researchers use the latest models, capabilities and technologies to tackle large and complex scientific challenges ranging from biological threats to climate change.

Our World-Class Facilities

Our Culture and Community

View Our Inclusion, Diversity, Equity and Accountability Page

Discover Your Next

Career Opportunity

LLNL is home to a diverse staff of professionals that includes administrators, researchers, creatives, supply chain staff, health services workers and more. Your next career opportunity is just around the corner.