Sig Hecker on North Korea's nuclear program

Even though North Korea's first nuclear test, in October 2006, may have surprised the world at large, it wasn't all that unexpected to Sig Hecker.

"North Korea's nuclear bomb was 50 years in the making," said Hecker, former director of Los Alamos National Laboratory and co-director of the Center for International Security and Cooperation at Stanford University.

Hecker, the featured speaker at Monday's Summer Student Seminar, has visited North Korea six times in the past six years. He recounted his experiences in meeting with North Korean diplomats and nuclear scientists during these visits and shared his views about that country's nuclear weapons program.

North Korea's nuclear program started back in the 1950s, under the Soviet version of Atoms for Peace. From the 1970s through 1992, they went solo under the cover of a civilian nuclear energy program. "The North Koreans have always been very self-reliant and they are masters of reverse engineering," Hecker said.

In explaining North Korea's desire for nuclear weapons, Hecker noted that they have felt squeezed between the imperial powers of China and Japan for most of their history, and for nearly 50 years threatened by U.S. nuclear weapons deployed in South Korea.

Although North Korea ratified the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) in 1985, they did not allow in International Atomic Energy Agencey (IAEA) inspectors until after U.S. nuclear weapons were withdrawn from South Korea in December 1991. These inspections found evidence of plutonium production and when confronted in 1993, North Korea withdrew from the NPT. "North Korea does not like to be confronted," Hecker observed.

A flurry of negotiations followed, resulting in the October 1994 Agreed Framework, under which North Korea would freeze its nuclear program and return to the NPT in exchange for two light water reactors plus food and energy aid. For nearly 10 years, North Korea refrained from extracting plutonium from 8,000 spent fuel rods that had been removed from their 5-MWe nuclear reactor earlier that year.

Then in January 2002, President George W. Bush named Iran, Iraq and North Korea as an "axis of evil" seeking weapons of mass destruction. North Korea walked out of the NPT again and began reprocessing its spent fuel rods.

"They crossed all sorts of 'red lines,' yet the U.S. didn't do anything," said Hecker. "In June 2003, they stated that all of the fuel rods had been reprocessed, and yet there was no response from the U.S. (We were otherwise engaged.)"

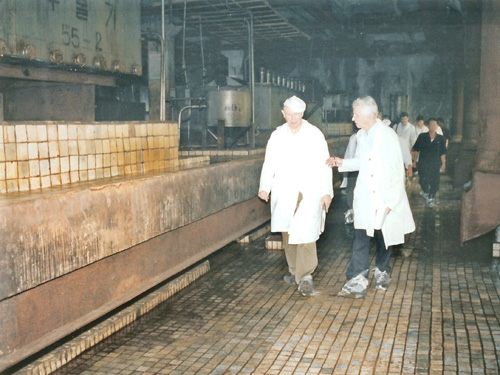

Hecker visited North Korea for the first time in January 2004. "They gave us remarkable access to their facilities." He described how the North Koreans showed him samples of their plutonium. "They were in marmalade jars with screw lids and sealed with tape. I asked if I could hold one of the sample jars. It was quite heavy and warm. I was convinced it was plutonium.

"They had a reason for allowing me in — they had a message they wanted me to carry back to the U.S. You could see them thinking: 'How much do we have to show this guy so he concludes we have the bomb without actually showing him the bomb?'"

Based on his six visits to North Korea — three times to the Yongbyon Nuclear Scientific Research Center and thrice to the capital city of Pyongyang — Hecker has gathered a fairly comprehensive picture of their nuclear weapons program. In his view, North Korea has mastered the full plutonium fuel cycle. Their two nuclear tests showed "adequate success," and tests of their long-range missile have demonstrated that two (out of three) stages work well.

Hecker downplayed the threat of North Korea attacking the U.S. with nuclear weapons. "Deliberate use against us is unlikely. North Korea is not suicidal."

In Hecker's opinion, North Korea poses a far greater threat as an exporter of nuclear and missile technology. "There is very little the U.S. can do to get North Korea to stop exporting. They depend so heavily on these exports for revenue."

When asked what he thought could be done about North Korea, Hecker wryly observed that "North Korea is playing a very weak hand — they have a failing economy, a decaying military, they can't feed their own people, they only have a half-dozen nuclear weapons — yet they have us wrapped around the axle."

In his opinion, up until North Korea's first nuclear test, they were willing to talk seriously about denuclearizing. But after the test, their confidence shot way up and they liked the idea of being a nuclear power. "They've seen that their few bombs have brought them enormous impact politically."

Hecker commented that it was important to look at the situation from non-U.S. perspectives. He noted that China views U.S. intervention as the greater threat. "They would rather have North Korea a nuclear power than have the U.S. in the Korean peninsula.

"From North Korea's point of view, things they've been promised by one U.S. administration have been thrown out by the next. So they feel cheated. But this doesn't negate the fact that they've been cheating the whole time on their agreements to freeze their nuclear program.

"If they would conduct six more nuclear tests, the problem would be solved," Hecker observed, only half-facetiously.