Sea lions, harbor seals receive helping hand from LLNL technology Newly developed diagnostic device helps marine mammals

Scientists from Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) and the Sausalito-based Marine Mammal Center are working together to diagnose several diseases that have struck California sea lions and harbor seals.

In recent months, about 17 percent of the adult sea lions that have died at the Marine Mammal Center have succumbed due to cancer, and others have become ill because of the bacterial disease leptospirosis, said Frances Gulland, the center’s director of veterinary science.

In June 2009, about 20 harbor seals died in Northern California from brain lesions, consisting of the premature death of living cells.

"The brain lesions are rare and unusual," Gulland said. "We don’t understand why it happened. We are looking at two very different problems (in the brain lesions of the seals and the cancer of the sea lions)."

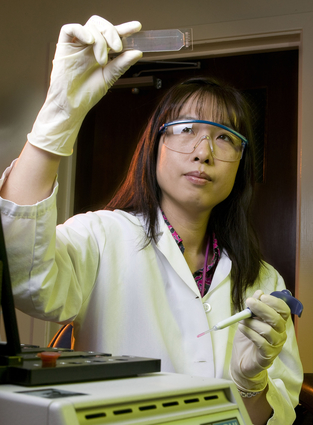

Gulland and her Livermore collaborator, biologist Crystal Jaing, are seeking to determine whether there is a bacterial or viral basis for the brain lesions and cancer through the use of a new LLNL detection technology.

They are utilizing the Lawrence Livermore Microbial Detection Array (LLMDA), a device that can detect within 24 hours any virus or bacteria that has been sequenced and included among the array’s probes. The current operational version of the LLMDA contains 388,000 probes that can detect more than 2,000 viruses and about 900 bacteria.

Already, Livermore scientists have shown that their LLMDA device is excellent at detecting known viruses and bacteria, said team leader Tom Slezak, the head of the Lab’s Pathogen Bioinfomatics Group.

By working with the Marine Mammal Center to diagnose the causes of the sea lion and seal diseases, the team is attempting to determine how well they can perform pathogen discovery of as-yet-unsequenced viruses or bacteria, Slezak said.

"The reason the work on marine mammals is so important is that this gives us excellent training for what we will need to do when the next unknown human pathogen outbreak hits. The next new Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)-like human virus will be as hard to identify and characterize as the unknown pathogens that are killing sea lions and harbor seals," Slezak said.

"It is only through these sorts of collaborations that the LLNL team can continually improve our microarray probe design and analysis software and laboratory sample preparation techniques, to be ready for a day we hope never comes," Slezak added.

To date, Livermore researchers have used the LLMDA to analyze frozen tissue samples from two deceased sea lions that were forwarded to them by the Marine Mammal Center.

One sample was found to have calicivirus, which would not have caused cancer, and the other sample had no virus or bacteria that could be positively identified and will now be sequenced by a company that assists LLNL, Jaing said.

Frozen tissue samples from eight other marine mammals, four from sea lions and four from harbor seals, will be analyzed in the coming months for bacterial or viral pathogens.

"This research has the potential to be very helpful because the genetic make-up of sea lions and harbor seals has not been well studied," Jaing said. "From this study, we can potentially identify novel viruses or bacteria that can cause cancer in marine mammals."

The cancer among sea lions is probably the most common cancer among wild animals in the United States, said Gulland, who expressed concern whether the cancer is caused by environmental exposures or infections.

"Seeing such a high prevalence of cancer in free-ranging wildlife raises a concern about why they’re getting it," Gulland said. "Sea lions swim in waters that we swim in and eat some of the same seafood that people eat, such as salmon, squid, rock fish and herring."

For years, the Marine Mammal Center has collaborated with the University of California, Davis Veterinary School, but researchers there suggested that the center also work with LLNL because of its LLMDA technology.

Another LLNL team, the Molecular Assay Development Group, led by biomedical scientist Pejman Naraghi-Arani, also is working with the UC Davis Veterinary School to evaluate some marine mammal samples.

This team has used a multiplex influenza assay that detects the influenza-A virus and its subtypes. In an analysis of two harbor seal swab samples, the assay found influenza-A in one sample.

In 2009, the Sausalito-based nonprofit center, which was established in 1975 as a hospital for sick marine mammals, treated about 1,700 such animals, including sea lions, harbor seals, elephant seals and dolphins. Two years earlier, the center treated two humpback whales, Delta and Dawn, that were injured with wounds from a boat propeller.

The Marine Mammal Center’s mission is to expand knowledge about marine mammals, their health and the ocean environment. Its core work is the rescue and rehabilitation of sick and injured marine mammals.

Founded in 1952, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory is a national security laboratory that develops science and engineering technology and provides innovative solutions to our nation’s most important challenges. Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory is managed by Lawrence Livermore National Security, LLC for the U.S. Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration.

Contact

Steve Wampler[email protected]

925-423-3107

Related Links

Marine Mammal CenterLawrence Livermore Microbial Detection Array

Detection technology used to analyze vaccines, LLNL News release, April 8, 2010

U.C. Davis Veterinary School of Medicine

Humpback whales, Delta and Dawn