Plutonium transport research well grounded

Five years from now, Lab scientists will be able to better determine how, when and why plutonium moves in soil and groundwater.

The way to predict how plutonium (Pu) is transported in groundwater away from a site and potentially toward populated areas is by looking at the dominant geochemical processes that control plutonium's behavior in the subsurface at environmental levels. But that isn't always so easy.

A $6-million five-year proposal funded by the Department of Energy's Office of Science, Biological and Environmental Research (BER), will allow about a dozen LLNL scientists to study Pu transport at concentration levels at the picomolar to attomolar scale (10 -15 to 10 -18 moles/liter, equivalent to dissolving one grain of salt in 100 Olympic-size swimming pools).

Plutonium can move on small particulates, called colloids, which are often found in groundwater, but the conditions that control whether Pu migrates or remains immobile are not well understood.

That's where the Laboratory team comes in. Annie Kersting, director of the Lab's Glenn T. Seaborg Institute and manager of the study, said previous experiments of Pu movement in the subsurface were performed at Pu concentrations orders of magnitude higher than those observed in the field. Now they will do experiments at much lower, environmental conditions.

Ultimately the research will help in the development of conceptual models for Pu transport across the Department of Energy complex. The model will provide DOE with the scientific basis to support decisions for the remediation and long-term stewardship of legacy sites, Kersting said.

"We can provide DOE with an understanding of when and how Pu is transported in groundwater," she said. "What process did it go through to get there, could it affect people downstream of DOE sites, and how can we predict and monitor Pu contamination?"

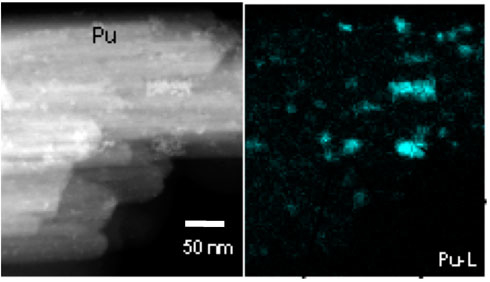

Taking advantage of the unique facilities housed at Livermore's institutes, the team will be able to measure minute amounts of Pu, similar to the concentrations found in soil and groundwater, with the Lab's secondary ion mass spectrometer (NanoSIMS), the transmission electron microscope (Titan SuperSTEM) and at the Center for Accelerator Mass Spectrometry. "With these tools, we'll be able to identify where the Pu is sited on a colloid, study the behavior of Pu at extremely low concentrations and identify the geochemical processes controlling its mobility," Kersting said. For example, the figure below shows Pu precipitates clearly identified on a iron-oxide colloid.

Mavrik Zavarin, the study's lead scientist said it is likely the team will discover that Pu behavior is very much dependent on concentration. "At very low concentrations, Pu will interact with groundwater, minerals and microbes in ways we could not have predicted based on past experiments", he said. "Our team at LLNL has a unique opportunity to study Pu chemistry under environmentally relevant conditions."

Laboratory results will be compared to field samples taken from three DOE sites: Nevada Test Site, Rocky Flats and Hanford. Plutonium-containing colloids will be collected and characterized in terms of their inorganic surfaces, associated organic compounds and coatings and possible microbial associations.

The Livermore team includes: Kersting, Zavarin, Susan Carroll, Robert Maxwell, Zurong Dai, Ross Williams, Scott Tumey, Pihong Zhao, Ruth Tinnacher, Patrick Huang and Ruth Kips. Collaborators include Brian Powell from Clemson University and Duane Moser from the Desert Research Institute.