Lockdown doesn’t hinder annual Data Science Challenge

(Download Image)

(Download Image)

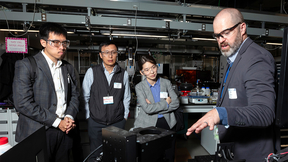

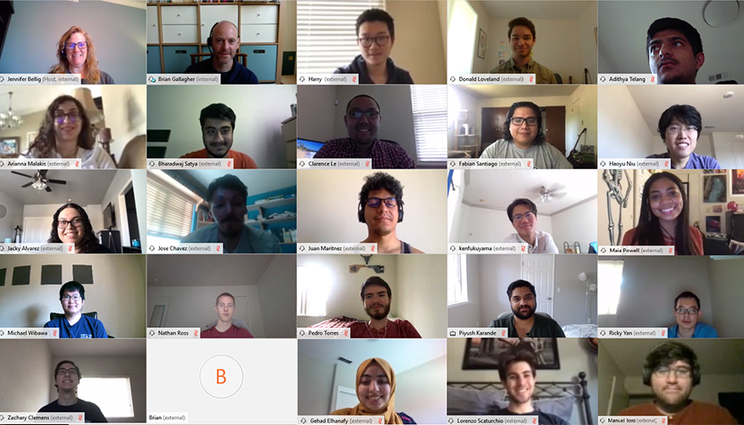

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic and shelter-in-place restrictions, this year’s Data Science Challenge with the University of California, Merced was an all-virtual offering. The two-week challenge involved 21 UC Merced students who worked from their homes through video conferencing and chat programs to develop machine learning models capable of differentiating potentially explosive materials from other types of molecules. Photo courtesy of Marisol Gamboa/LLNL

The COVID-19 pandemic and its subsequent restrictions on gatherings and travel have forced institutions and companies around the world to rethink how they offer their summer programs and internships, and Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) is no exception.

This year’s Data Science Challenge with the University of California, Merced, the second such event of its kind, was an all-virtual offering and an experiment in distance learning and online collaboration. The two-week challenge involved 21 UC Merced students (16 undergraduate and five graduate students) who worked from their homes through video conferencing and chat programs to develop machine learning models capable of differentiating potentially explosive materials from other types of molecules.

While the unique circumstances forced organizers to adapt, the goals of the challenge remained the same: to encourage students to pursue graduate degrees, expose them to real-world Laboratory data science projects, provide the experience of working in a multidisciplinary team and make students aware of LLNL as a possible career opportunity.

“It was a really heavy lift this time around,” said lead organizer Marisol Gamboa. “The times are definitely challenging, but I’m really excited about the leaps and bounds we made to create this cohesive team environment. I’m even more proud of the Lab for allowing us to take a stab at this. It really says a lot about Livermore. We decided this was important to do for these students and that the benefits would outweigh the risks. The two weeks we selected may be our only opportunity to have the students’ attention.”

Where there's a will

Offered through the Lab’s Data Science Institute (DSI) and the Center for Applied Scientific Computing (CASC), program organizers selected the students just prior to the lockdown restrictions. When the Lab site shuttered, Gamboa, along with administrator Jennifer Bellig and UC Merced applied math professor Suzanne Sindi, had to quickly brainstorm how to make the challenge work virtually, essentially rebuilding it from the ground up.

“We had all these flowcharts and task lists from the previous year and basically we had to get rid of them and start over,” Bellig said. “We just got creative. Everybody had this mindset of ‘we’re going to will this to happen; let’s figure this out.’ It’s cool to be part of something like that and see it come to fruition. It’s really been an encouragement to me during this down time.”

UC Merced provided support to students to ensure they had the tools they needed to conduct research in the new virtual environment. The university supplied laptops for students and shipped hotspots to two team leads with unstable wi-fi connections. UC Merced IT System Administrator Sarvani Chadalapaka also created guest accounts on the university’s MERCED high performance computing cluster so students could scale up their computational analyses.

“It was definitely a challenge, but Marisol and Jennifer were fantastic partners,” Sindi said. “We had so many planning meetings and as we worked through each potential problem. We gained more and more confidence that not only would the program work this year, it would be awesome. Everyone I worked with at UC Merced was deeply committed to making this year’s challenge a success.”

Organizers distributed the five graduate-level student team leads among five teams of undergraduate and recently graduated students. Each team also was paired with one Lab mentor who was available for guidance and to answer any questions the students had along the way. Prior to the challenge, the mentors met virtually with student team leads to address any anxieties and preconceptions they had.

Facing the challenge

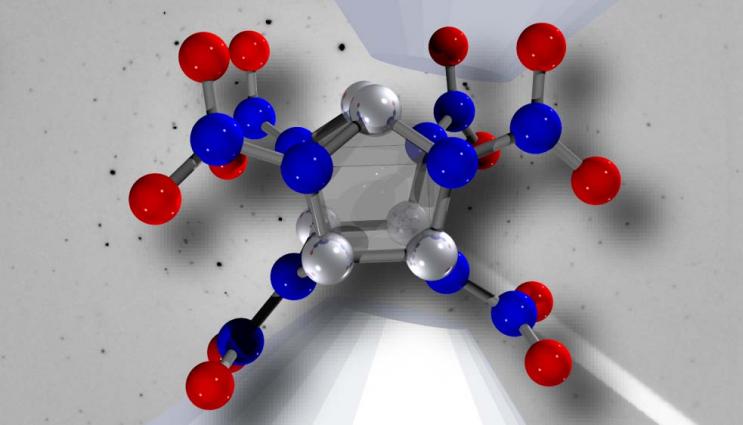

On the first day of the challenge, June 1, students and mentors introduced themselves via WebEx, and Lab employees presented overviews of the Lab, CASC (by center director Jeff Hittinger) and the DSI (by institute director Mike Goldman). The mentors then discussed the challenge problem, centered on using machine learning to develop a classifier for potential explosive materials given only their molecular structures.

The machine learning algorithms were to be trained on a dataset of 400 known explosive compounds and about 5,000 pharmaceutical drug compounds, with students tasked to calculate chemistry features and come up with models capable of differentiating them. The problem is tied to actual Lab work and is difficult, mentors said, because drug molecules can look very similar to explosives but behave differently based on how they are bonded or where they are positioned in 3D space.

“At the Lab, we’ve been working on machine learning applied to materials science and we wanted to include a chemistry component to make the program more interdisciplinary,” said mentor and LLNL computer scientist Brian Gallagher. “It’s nice that it’s a real problem, it’s compelling and easy to understand. It gives students a chance to try something where we don’t really know the answer, so we can work on it together. From my perspective, it worked out as well as I could’ve hoped. By the end of the first day I started to get a good feeling because I could tell everybody was going to get something out of it.”

The Lab mentors, including Gallagher, Donald Loveland, Phan Nguyen, Piyush Karande and Anna Hiszpanski, told students that while there were numerous ML techniques and models to choose from, there was no “silver bullet” known to best solve the problem. Students were encouraged to experiment with a range of techniques to find out what worked best for them, and to try to understand why the models made the predictions they did. After the mentors introduced a few general machine learning approaches and different aspects of machine learning, they set the students loose.

The UC Merced students were challenged to use machine learning to develop a classifier for potential explosive materials given only their molecular structures. The algorithms were trained on a dataset of 400 known explosive compounds and about 5,000 pharmaceutical drug compounds, with students tasked to calculate chemistry features and come up with models capable of differentiating them.

Each day began with status updates and check-ins with mentors, followed by working sessions over Zoom, WebEx and Microsoft Teams. Students used an open-source cheminformatics software called RDkit to package the molecules and coded in Python. To recreate the experience of in-person collaboration and stimulate engagement, students were encouraged to use their webcams as much as possible. Algorithm code and other files were uploaded daily through Box, a shared collaborative space where students and team leads could interact in real time, and teams reported on their progress at each day’s end. Students said while the online-only interaction took some getting used to, it didn’t take long to get into a flow.

“This whole thing has been a process of understanding how to collaborate,” said Maia Powell, a third-year Ph.D. student in applied math at UC Merced and one of the team leads. “It’s always difficult working with code (in an online environment) but we’ve made it work. Everyone at Livermore made it point to say ‘It’s not about the results that you get, it’s about what you learn.’ I feel like we got so much done over two weeks and learned so much in a short amount of time.”

Powell, a recipient of a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship, said she had always wanted to explore machine learning and applied for the challenge hoping to gain leadership experience. The challenge not only “demystified” ML for her, but also taught her a lot about teamwork.

“Working on this interdisciplinary team has been really interesting and what I imagine working at the Lab is like,” Powell said. “I’ve met a lot of Livermore employees at conferences, and I feel like they all really like their jobs and are excited to talk about it, so interacting with them has been the most helpful in terms of what to expect if I were to have an internship or eventually work at the Lab.”

Learning made easy

UC Merced student Arianna Malakis, who grew up and resides in Livermore, graduated in the spring with a degree in cognitive science and is seeking a career in data science. She said she was drawn to the challenge to learn more about the Lab and big data. Through the support of her teammates and mentor, Malakis said she was able to work through any pitfalls and discovered machine learning wasn’t as scary as she’d been led to believe.

“I came into this absolutely terrified that I would have to learn all these equations that I was never exposed to before,” Malakis said. “Then I’m reading all the guides and doing my research and realized it’s manageable — it’s not typing in lines and lines of math I’ve never taken. It’s also made me realize I’m on the right path. I’ve loved this challenge and I’ve loved every problem I’ve encountered, because when I get past it, I feel so satisfied, and when my team makes a breakthrough, I feel happy. This challenge has shown me that machine learning is easy to learn and that anyone can do it, and that I’m doing exactly what I want to be doing.”

Pedro Torres, a first-generation college student going into his senior year at UC Merced in computer science, also was new to machine learning but said he now knows how to implement it. Although, like many of the students, Torres was initially disappointed that he didn’t get to work on site, he found the online collaboration engaging and educational.

“I’ve been having fun with my own team and getting to know them and collaborating together,” Torres said. “Even if it’s only two weeks, I feel like there’s a sense that you get some form of experience before it becomes your actual job. I’m glad that programs like this exist so I can get a better idea of where I stand, how I can improve and, going forward, what I need to study more. It gave me a good idea of what the Lab is doing.”

With access to the Lab restricted, this year’s tour of the National Ignition Facility was virtual. In addition to the daily working sessions, organizers held online workshops on professional development, including job qualifications, how to prep for interviews and resume writing. And to recreate the social dynamic that students had from working in the same building last summer, organizers held virtual social times, where students played trivia and participated in a scavenger hunt, collecting items from their own homes. The students also attended online lectures from Lab scientists Laura Kegelmeyer and Marisa Torres, who inspired the students to think about what they wanted from their own careers.

“Talking to someone professionally who works at the Lab and hearing about their job and seeing their happiness just radiate through was the most impactful thing for me,” Malakis said. “The entire time I thought, ‘wow she loves her job.’ I want to have that much love for whatever I do when I have a career.”

Impressive results

The challenge culminated on June 12 with the teams presenting their results, discussing what they learned from the experience and what they would have done given more time. The students explained what features and fingerprints (strings of binary values that depict chemical structures) they used to best predict whether molecules were explosive and compared the machine learning methods they explored for accuracy, noting the strengths and limitations of each model. Organizers and mentors said they were “thoroughly impressed” by the work of the students and team leads, particularly under the unique circumstances.

“Not only was I impressed by the amount of techniques and the work that you all did, but really this was done during an incredibly difficult time,” Sindi told the students. “With everybody remote, communication is so hard, but you all did an amazing job. I hope you all feel proud of yourselves.”

“It’s amazing what these students have accomplished,” Gallagher said. “I feel like we should just hire the lot of them. My hope is that this is a really good experience for them and that they go back and tell their friends what a cool place Livermore is to work. I’m glad we decided to go ahead with it. A lot of companies canceled their student programs altogether this summer, so this is a testament to how special LLNL is.”

The program also was made possible through the support and assistance of the Office of University Relations and its director, Annie Kersting. Organizers said they hoped the students, depending on how circumstances change, could someday visit the Lab to present their projects in person. With a newfound confidence that such student programs can successfully be offered remotely, organizers added that they are optimistic they can expand the challenge and other DSI programs to additional UC schools and potentially beyond.

“There are really high hopes running here,” Gamboa said. “This experience made us think out of the box, not about what we’ve done, or what is possible, but what we could absolutely make work. And I think we’re going to have a lot of tools we can benefit from going forward because of this.”

“The last day of the challenge felt like the last day of summer camp,” added Sindi. “We didn’t want it to end, and I can’t wait until next year.”

Contact

Jeremy Thomas

Jeremy Thomas

[email protected]

(925) 422-5539

Related Links

"Two-week workshop lets UC Merced students step into shoes of Lab computer scientists"LLNL Data Science

" 'Yes, You Can’: UC Merced Students Learning, Growing at Livermore Lab"

Tags

HPC, Simulation, and Data ScienceComputing

Community Outreach

Featured Articles