Lab's work provides BASIS for biodetection

By Stephen Wampler

Telephone calls awakened Tom Slezak, Kris Montgomery and Cheryl Strout and Julie Avila at their homes from a sound sleep. Less than a month after 9/11, it was 1 a.m. on a Saturday morning, Oct. 6, 2001.

Several hours earlier, a photo editor at Florida-based American Media Inc. named Bob Stevens had died from inhaling anthrax powder sent through the mail. The anthrax attacks, which killed five people and sickened another 17, were in their early stages.

Slezak, Montgomery, Strout and Avila were four of the 14 Laboratory employees -- five men and nine women -- who received the early morning phone calls.

They were told to report to the Laboratory within three hours and to pack to be away from home for two weeks.

As Slezak recalls, "We were told, 'We can't tell you where you're going or when you will return.'"

They traveled in Laboratory vans to Travis Air Force Base, where they boarded a small and lumbering Idaho National Guard C-130 transport plane later Saturday for their flight. Ten hours later, they arrived on the East Coast.

Their mission, in tandem with colleagues from Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL), was to place biological detection equipment in Washington, D.C. and to establish a sample processing laboratory.

As they traveled to the East Coast, the 14 Lab scientists and engineers flew with two enormous transportation containers -- about eight feet high and 10 feet long -- that contained tens of thousands of pounds of equipment.

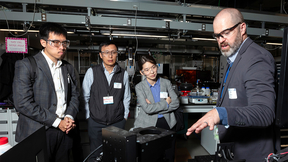

The instruments and equipment -- biological detectors and laboratory machines -- comprised the Biological Aerosol Sentry and Information System, or BASIS that had been under development by Livermore and LANL researchers since 1999. Funded by the National Nuclear Security Administration, BASIS had been designed to detect airborne biological pathogens for special events, such as major sporting events and political conventions.

'Suddenly we were part of it'

Kris Montgomery, then a Lab biomedical scientist, had never been on a military aircraft before that day in October nearly 10 years ago.

"The noise on the plane was very loud and we had to wear earplugs," Montgomery remembers. "You couldn't talk because it was so noisy. We read or slept."

Lab biomedical scientist Cheryl Strout remembers the 1 a.m. phone call, packing for a destination she didn't know and getting on the flight to Washington, D.C. as "kind of a surreal experience."

"You had seen what had happened and watched the news, and then you get a phone call, saying 'Pack, we're leaving.' Suddenly, we were a part of it," Strout says.

"As a single parent with three boys, I knew I had to do it. It was a matter of packing as quickly as I could and having one of my sons drop me off at the Laboratory. I made calls to members of my family to watch out for my sons."

Julie Avila, then a scientific technologist, recalls that receiving the early morning call to head to the East Coast was energizing.

"We knew the call would be coming, but we didn't know when. I had two girls and it was somewhat scary because of what was going on in the world. There were so many unknowns," Avila said.

Once their C-130 cargo plane landed, the Lab employees were met at the airport by a U.S. Army colonel, who told the LLNL team: "Welcome to Andrews Air Force Base. Our nation is at war and you've been drafted."

Initially, as their van drivers took them to their hotel, they took a wrong turn and the Lab BASIS team wound up for a few brief moments making a U-turn near an entrance to the Central Intelligence Agency headquarters in Langley, Va.

Put to the test

The BASIS technology had been developed to protect athletes and spectators at the 2002 Winter Olympics in Salt Lake City. It had never been put to a real-world test -- but soon it would be protecting the nation's capital and, in time, other major U.S. cities.

BASIS reduced the time for detecting a biological pathogen release from days or weeks to less than a day, allowing public health officials to have much more rapid warning.

"Once we arrived, we were ready to process samples within 24 hours," Montgomery says. "We had such a great crew. Everybody knew what their jobs were and they did them. It was a total team effort. We had worked on the system here at Livermore and everyone knew what their responsibilities were."

Avila agreed with Montgomery's assessment. "We had jobs to do and we were ready to do them. It went extremely well. We had practiced for the Olympics and we expected that was going to be our first roll-out, but it wasn't. It was pre-empted by 9/11. It came together flawlessly.

"I worked the night shift," Avila added. "That's not easy, but it was OK. It was hard sleeping during the day. We worked seven days a week and we did it for 51 days. We just worked hard."

For the creation of BASIS, Los Alamos scientists had developed the system's aerosol collection units, the system's command and control software and the sample handling procedures for outside the field laboratory. On the East Coast, LANL researchers worked with the Environmental Protection Agency to set up a sample collection system and to distribute biodetection monitors.

Livermore scientists had been responsible for the BASIS biodetection equipment and DNA analysis procedures, as well as the system's communications capability. In 2001, Lab scientists established the lab for processing BASIS samples in the National Capital Region.

"I feel very proud that our team of scientists and engineers, in collaboration with our colleagues from LANL and the Environmental Protection Agency, had the right combination of talents to provide the only system in the nation, or the world at that time, that was capable of detecting a large-scale bioterrorism attack," Slezak said.

Once they settled into their mission, the Livermore and Los Alamos employees worked in two shifts -- from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., and from 9 p.m. to 9 a.m.

One of the day shift employees was LLNL's Mark Wagner, then an electronics engineer and now a computer scientist who flew out two days after the Lab employees aboard the military flight. He helped put together the software to track the samples being processed through the lab.

A typical day started with breakfast at 7:30 a.m., followed by the drive to the East Coast lab to process samples. The researchers would arrive by 9 a.m., work until 9 p.m. or later, come back to the hotel by 10 p.m. (sometimes stopping at McDonald's on the way home), go to sleep and do it all over again.

"One of the funniest things that happened occurred while we were driving to work," Wagner says. "Someone commented that the traffic seemed awfully light. Then I looked at my watch (with a day indicator) and I realized it was Saturday. We had no clue what day it was.

"The interesting thing about the BASIS system was that it was designed for special events and it has now been in operation for about 10 years, including about nine years around the nation," Wagner says.

In the second and third weeks of their deployment, the Lab employees' ranks swelled as another dozen or so LLNL employees came out to the East Coast to assist in staffing the sample processing lab. In the third week, the Lab also started hiring local scientists to staff the sample processing lab.

One of the scientists hired in November 2001 was Thomas Bunt, who became a Laboratory employee and who has been the principal investigator for the Lab's BioWatch (the nation's biological detection system) efforts since 2005.

"The Livermore BASIS team were living and operating out of a hotel, so I was interviewed in a hotel room and told very little information about the content of the work due to the sensitivity," Bunt recalls.

"They also told a lot of us that this would be a temporary job lasting about six months; it's now 10 years later and the National Capital Region lab is still there and has processed samples every day since the initial BASIS deployment. It's been going 365 days a year for years through the rain, sleet, snow, holidays and weekends," Bunt says.

Answering the challenges

With the BASIS equipment that was planned for deployment at the Winter Olympics then in use in the National Capital Region, the two national labs had to purchase more equipment for the Olympics.

"There were at least 15-20 people from across the Laboratory -- the then- Biology and Biotechnology Research Program, Computation, Engineering, Procurement, Human Resources and other areas -- who served as support staff to us back on the East Coast and who did the leg work to replicate another BASIS system for the Winter Olympics," Slezak said.

During their time in Washington, the Livermore bioinformatics team developed a system that used bar codes to track each step of the BASIS process.

"We found we could check for many categories of human error and reduce human error by automating warnings of possible mistakes," Slezak said.

A little more than a week after the Livermore and Los Alamos BASIS team arrived, on Oct. 15, then-Senate Majority Leader Tom Daschle told reporters that anthrax had been found in his office. The terrorists had struck from another direction.

"We all prepared for an aerosol attack and then it came through the mail," Slezak said.

The Livermore employees worked on the East Coast for about two weeks and then returned to LLNL and home for about a week, before returning for another two-week stint. By about Thanksgiving, the East Coast deployment had ended for most LLNL researchers -- and they started preparing for the February Winter Olympics.

"When we left in early October, I think it was hard on our families." Montgomery said. "We left in the middle of the night on a moment's notice. At the time, I was a single mother and I had a daughter who was a senior in high school.

"We spoke on the phone every night and I wanted to be sure that she was OK. But I think she was more worried about me. By nature, I'm a home body, but I felt I needed to be there in Washington doing what I was doing."

The birth of BioWatch

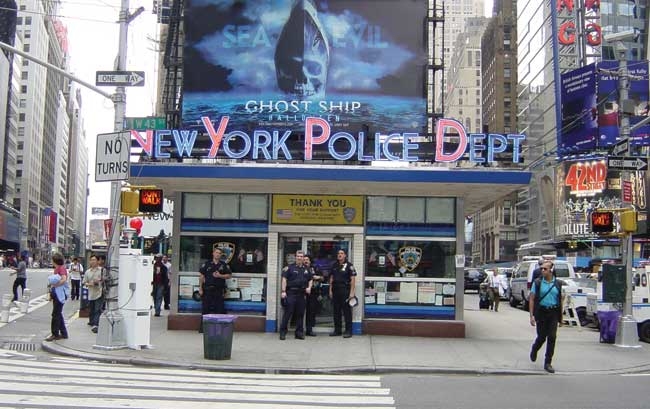

In late 2002, then-President Bush decided that BASIS would be deployed as the BioWatch system in more than 30 cities around the United States.

In each of those cities, LANL scientists set up the aerosol sample collection system and trained the personnel, while Livermore researchers established the processing laboratory and informatics, as well as training the local lab staff.

"BASIS worked when we needed it for biodetection in the nation's capital and it worked at the Winter Olympics. Now it's worked as a key part of the BioWatch system for close to nine years around the nation," Slezak said. "It's a project that turned out very well."

Contact

Stephen P Wampler[email protected]

925-423-3107

Tags

Global SecurityStrategic Deterrence

Featured Articles