LAB REPORT

Science and Technology Making Headlines

March 18, 2016

LLNL scientist Karis McFarlane analyzes thousands of soil samples at the Center for Accelerator Mass Spectrometry as part of a project to improve models showing how organic and mineral soils accumulate and disperse carbon.

Atomic age's unintentional consequence

From 1945 to 1963, the United States and the Soviet Union detonated more than 400 nuclear bombs above ground in a weapons-measuring contest.

But some good science developed from those detonations: They spit out neutrons that set off a chain of events to create carbon-14, an exceedingly rare isotope of carbon, which is used to carbon date items.

The amount of carbon-14 in the atmosphere spiked. That carbon-14 reacted with oxygen to make carbon dioxide. Plants breathed it in, animals ate the plants and humans ate the animals and plants. “Everyone alive has been labeled with it,” says Bruce Buchholz, a scientist at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. “The entire planet has been labeled.”

Carbon-14 is not dangerous to humans — but it is very useful, because levels of the isotope have been slowly falling off since the 1950s spike. By measuring the amount of carbon-14 in a sample, scientists can pinpoint its age within just a year or two. They can use the method to find the age of an unidentified body using tooth enamel, or study how often human fat cells are born and die, or discover how old trafficked ivory is.

LLNL researchers re-created the incredible heat and pressure that transforms graphite into diamond while retaining the graphite’s original hexagonal structure during a meteor impact.

It’s shocking: Diamonds shed secrets of meteor impacts

In 1967, a hexagonal form of diamond, later named lonsdaleite, was identified for the first time inside fragments of the Canyon Diablo meteorite, the asteroid that created the Barringer Crater in Arizona. Since then, occurrences of lonsdaleite and nanometer-sized diamonds have been speculated to serve as a marker for meteorite impacts.

It has been hypothesized that lonsdaleite forms when graphite-bearing meteors strike the Earth. The violent impact generates incredible heat and pressure, transforming the graphite into diamond while retaining the graphite’s original hexagonal structure.

That’s where Lawrence Livermore scientists come in. They provide new insight into the process of the shock-induced transition from graphite to diamond and uniquely resolve the dynamics of the phase change.

The experiments show unprecedented measurements of dynamic diamond formation on nanosecond timescales by shock compression of graphite starting at pressures above 500,000 atmospheres.

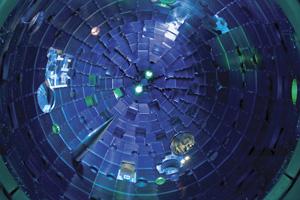

The target bay of the National Ignition Facility is a ready source of neutrons at energies comparable to those produced in the deuterium-tritium fusion reactions that power a hydrogen bomb. Photo by Damien Jemison.

I spy hidden nukes

Experts say the most likely nuclear terrorism scenario is a bomb set off on a city street. Past experience offers only a sketchy picture of the resulting devastation.

The atomic bombs the United States dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945 detonated about 500 meters above those cities. During the subsequent half-century, while the U.S refined its atomic arsenal, nearly all tests were in the air or underground, not in citylike environments.

Researchers did study fallout and how it forms, but they were seeking clues about how to prevent or alleviate radiation illness, not identify the perpetrator.

“Scientists were not interested in figuring out what kind of device had detonated, because they already knew that,” says analytical chemist Michael Kristo, a nuclear forensics expert at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

Kristo and other nuclear detectives can pinpoint when and where a nuclear bomb’s materials originated and when it was made. Researchers at Livermore and other national labs are producing surrogate fallout representing different bomb types. The scientists have pressed into service the National Ignition Facility at Livermore, one of the world’s most powerful lasers, which Kristo calls “a ready source” of neutrons at energies comparable to those produced in the deuterium-tritium fusion reactions that power a hydrogen bomb.

Radiobiologist Matt Coleman displays a passive flow lateral device for biodosimetry developed at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. Photo by Julie Russell

Medicine in deep space

In the future, NASA astronauts journeying into deep space may give themselves a health checkup with the aid of a small medical device developed by a team of scientists, including one from Lawrence Livermore.

Laboratory radiobiologist Matt Coleman is part of the six-scientist team, including researchers from NASA’s Ames Research Center, the University of California, Davis and Sandia National Laboratories/California, that has developed a small, portable medical diagnosis instrument.

The patent covers the development of a comprehensive in-flight medical diagnostic system in a hand-held format and weighing less than one pound for human deep-space missions, such as a mission to Mars, which is expected to take six months each way.

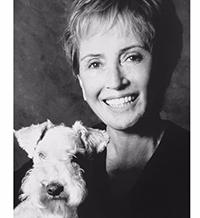

Benjamin Santer

Climate crusader

Benjamin Santer, a climate scientist at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, recently spoke at Principia College in Elsah, Illinois, as part of the school’s Changemakers speaker series.

As the lead author of a 1995 intergovernmental report that was the first major scientific declaration of human activity being responsible for climate change, Santer has been subject to death threats and public criticism for his work.

The report infamously noted that “the balance of evidence suggests that there is a discernable human influence on global climate,” and it’s a sentence that “is forever engraved on my memory,” Santer said. “It’s kind of sobering now to look back 20 years after that statement was released and recognize that that sentence will follow me to my grave.”

The local newspaper sat down and asked a series of Q&As with Santer about his work over the years.