LAB REPORT

Science and Technology Making Headlines

March 8, 2019

Capturing an atomic explosion at a test site in the Nevada desert in 1957.

Blasts from the past

The force of nuclear weapons must be seen to be believed. Now, thanks to a project headed by Gregg Spriggs at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, the public can see the destructive power of atomic blasts as never before.

Starting in 1945 the United States conducted 210 above-ground nuclear tests, all of them documented on film, from as many angles as possible. That ended in 1963, when the U.S. and the Soviet Union agreed to stop testing in the atmosphere.

Spriggs understands the physics that produces these spectacular images — fireballs that can spread two miles across and reach temperatures of 10 to 15 million degrees Kelvin. At the outer edge of the fireball is a shockwave; what the fireball doesn't vaporize, the shockwave crushes. "When it starts off, it's moving at Mach 100, a hundred times the speed of sound," Spriggs said. And then there is the mushroom-shaped cloud, which climbs into the sky, spewing radiation. "That's directly tied to the nuclear fallout which is very, very sensitive to the cloud height," he said.

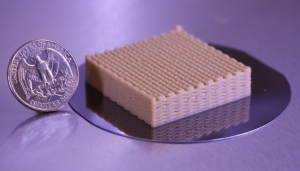

An LLNL team 3D printed live yeast cells on lattices.

A toast to efficiency

Lawrence Livermore researchers have 3D printed live cells that convert glucose to ethanol and carbon dioxide gas (CO2), a substance that resembles beer, demonstrating a technology that can lead to high biocatalytic efficiency.

Bioprinting living mammalian cells into complex 3D scaffolds has been widely studied and demonstrated for applications ranging from tissue regeneration to drug discovery to clinical implementation. In addition to mammalian cells, there is a growing interest in printing functional microbes as biocatalysts.

Microbes are extensively used in industry to convert carbon sources into valuable end-product chemicals that have applications in the food industry, biofuel production, waste treatment and bioremediation. Using live microbes instead of inorganic catalysts has advantages of mild reaction conditions, self-regeneration, low cost and catalytic specificity.

LLNL’s Brooke Buddemeier says it is possible to survive in a nuclear attack.

Go in, stay in, tune in

A 10-kiloton-or-less nuclear detonation by a terrorist is the first of 15 disaster scenarios that the U.S. government has planned for.

No one could fault you for panicking after the sight and roar of a nuclear blast. But there is one thing you should never do, according to Brooke Buddemeier, a health physicist and radiation expert at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

"Don't get in your car," he said. “Don't try to drive, and don't assume that the glass and metal of a vehicle can protect you.”

Your best shot at survival after a nuclear disaster is to get into some sort of "robust structure" as quickly as possible and stay there, Buddemeier said. He's a fan of the mantra "go in, stay in, tune in."

Last year, Lawrence Livermore computer scientists (from left) Todd Gamblin and Greg Becker met with HPC Application Expert Massimiliano Culpo at the École polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) in Lausanne, Switzerland. Culpo is an EPFL scientist and longtime Spack contributor who uses Spack to manage software on EPFL’s supercomputers.

Spack attack

Lawrence Livermore computer scientists have created Spack, an open-source package manager for cluster users, developers and administrators.

It is rapidly gaining popularity in the HPC community. Like other HPC package managers, Spack was designed to build packages from source. Spack supports relocatable binaries for specific OS releases, target architectures, MPI implementations and other very fine-grained build options.

Spack integrates with the U.S. Exascale project’s open source software release plan and will help glue together the HPC OSS ecosystem.

Melting sea ice is just one of the effects of global climate change.

A turning point in climate science

Thanks to 40 years of satellite data, scientists are certain that climate change is real, and humans are causing it.

More than that, experts have been clear on the inevitability of climate change for four decades, as a new paper reports.

The comment, published recently in the journal Nature Climate Change, celebrates the 40th anniversaries of three key pieces of climate science that contribute to modern certainty about anthropogenic climate change: the beginning of satellite temperature measurements in late 1978 and the 1979 publications of a report and a paper that shaped how scientists looked for human fingerprints in the climate signal.

“It’s about taking a trip down memory lane and trying to understand, ‘how did we get here?’” said paper author Benjamin Santer, a climatologist at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. “In taking that trip down memory lane, it turns out that the events of 1979 were important… and were related.”