Lab receives OPCW recertification

In force since 1997, the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) has been ratified by 188 countries, including the United States, and is administered by the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW).

To maintain their certification, LLNL and other OPCW-designated laboratories must maintain a three-year rolling minimum average of at least two "A" grades and one "B" in ongoing proficiency tests.

The Laboratory received its original certification in 2003 and retained its certification to accept samples and analyze them for the possible presence of chemical weapons under the CWC for seven straight years.

However, in February 2011, the Laboratory received a "C" grade in its proficiency test and was consequently suspended from receiving samples during an OPCW challenge inspection.

Since that time, in three straight proficiency tests -- October 2011, April 2012 and October 2012 -- the Lab has garnered "A" grades and has regained its full status as a designated OPCW laboratory.

"It's not unusual for a number of the OPCW laboratories to be suspended for failing to achieve their proficiency standards," said Brad Hart, the director of the Laboratory's Forensic Science Center.

Out of the 23 currently certified OPCW laboratories worldwide, only eight of the labs (or about one-third) have never been suspended. Only one laboratory, Finland's Verifin lab, has received straight "A" grades since the start.

Besides LLNL, the other U.S.-designated laboratory that could receive OPCW challenge samples, the Aberdeen Proving Ground, Md.-based Edgewood Chemical Biological Center, was suspended from 2006-2008.

"These tests are challenges. The OPCW is trying to push the science and technology to the absolute limit. In the event of a challenge inspection, a lot would ride on the results of these tests, so they want to be sure the labs are performing at the highest possible level," Hart said.

Under the CWC treaty, the development, production, acquisition, stockpiling and use of chemical weapons is banned, as is the transfer of chemical-weapon-related technologies.

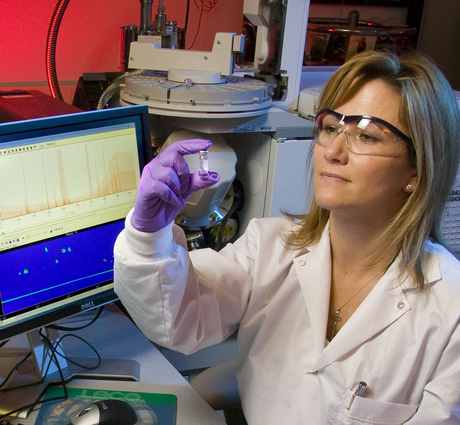

Livermore's OPCW work is carried out by the Forensic Science Center (FSC) as a part of the Global Security Principal Directorate's Nonproliferation Program.

In the latest proficiency test, held Oct. 15-29, FSC scientists had to analyze two types of samples -- an organic waste sample and a waste water sample -- for CWC-monitored chemicals, which literally encompass thousands of chemicals of concern.

The Livermore researchers were given 15 days to identify the "suspected" chemical weapons compounds in the samples and report their findings, said Lab principal investigator Armando Alcaraz.

Alcaraz and Hart called the October test "one of the most difficult technical challenges of any of the previous OPCW proficiency tests that Livermore has taken."

The organic waste sample was spiked with high concentrations of interfering hydrocarbons. These compounds completely hindered the LLNL team's nitrogen screening techniques and required development of a special sample cleanup procedure to detect and identify the nitrogen-containing reportable chemicals.

In addition, the waste water sample contained a reportable spiking chemical that included deuterated functional groups (i.e., had deuterium introduced into the compound). A deuterated reportable chemical had never been spiked in a proficiency test before, and the compound (di-isopropyl-(d14) methylphosphonate) was not in any of the spectral databases.

"The Lab's Forensic Science Center is a full spectrum all-weapons of mass destruction forensic analysis center," Hart said. "We span everything from basic research to applied research and analysis of real-world samples. Some of the OPCW-designated labs focus solely on their OPCW work. We work on OPCW projects for about two weeks of the year."

Alcaraz noted that the center has refined its approach to executing the proficiency tests, in addition to introducing new analytical technologies, such as two-dimensional gas chromatography and high-resolution mass spectrometry.

The FSC was selected in 2000 by the State Department to be a U.S. facility to seek OPCW certification. The FSC was tapped because of the Laboratory's advanced environmental controls and physical security, as well as its well-demonstrated capabilities in detecting and analyzing trace levels of unknown materials.

Under a condition set by the U.S. Senate during its ratification of the CWC, all samples taken by OPCW inspectors at U.S. chemical plants must be analyzed in the United States.

The Laboratory's OPCW work is funded by the National Nuclear Security Administration's Nonproliferation and International Security Office and its Office of Dismantlement and Transparency.

The samples for the October proficiency test, taken by LLNL and 22 other laboratories around the world, were prepared by the VERTOX Laboratory, Defence Research & Development Establishment in Gwalior, India. The participating laboratories' test results were then evaluated by the LAVEMA (Laboratorio de Verificacion de Armas Quimicas, Instituto Tecnologio la Maranosa) in Madrid, Spain.

In the most recent round of testing, 12 laboratories received preliminary grades, of "A's," two received "B's", four received "C's," one was given a "D" and four were given "F's."

In addition to Alcaraz and Hart, other Lab researchers participating in the OPCW tests were Maureen Alai, Cynthia Alviso, Deon Anex, Sarah Chinn, Saphon Hok, Carolyn Koester, Roald Leif, Brian Mayer, Tuijuana Mitchell-Hall, Heather Mulcahy, Michael Riley, Edmund Salazar, Robert Schmidt, Carlos Valdez, Alexander Vu, and Audrey Williams.

In 2011, LLNL, as well as the laboratories from Spain and Poland, received "C" grades that weren't based on technical issues, but were mainly based on their interpretation of the OPCW reporting guidelines. Subsequently, LLNL worked with the OPCW on a revamp of the reporting guidelines that added more clarity.

Through the OPCW process, Livermore researchers have developed working relationships with the U.S. State, Commerce, and Homeland Security departments, as well as the Environmental Protection Agency, the Federal Bureau of Investigation and other law enforcement agencies.

Contact

Stephen P Wampler[email protected]

925-423-3107

Tags

Physical and Life SciencesFeatured Articles