Lab employees help fill education gaps

(Download Image)

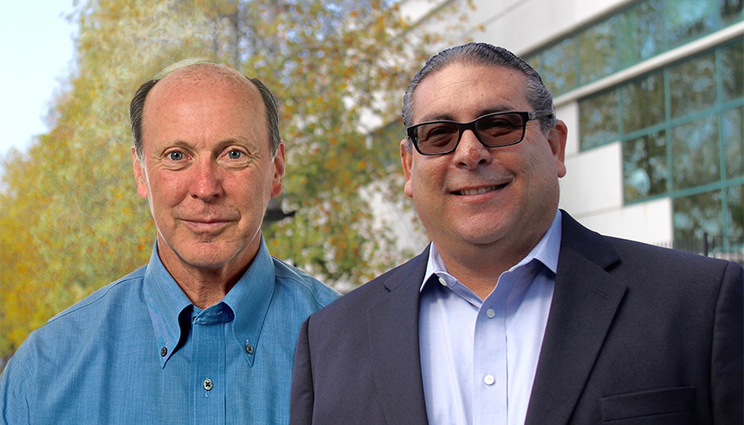

In the face of underserved communities and school district budget cuts, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory employees Bill Dunlop and Randy Pico are volunteering to fill in local education gaps.

(Download Image)

In the face of underserved communities and school district budget cuts, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory employees Bill Dunlop and Randy Pico are volunteering to fill in local education gaps.

Editor's Note: During the Helping Others More Effectively (HOME) Campaign, Public Affairs will run a series of articles about Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory employees who volunteer for various nonprofit agencies.

________

In the face of underserved communities and school district budget cuts, Randy Pico and Bill Dunlop are volunteering to fill in local education gaps.

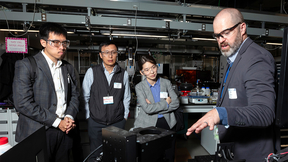

In 2013, Engineering Directorate Senior Superintendent Randy Pico worked with the Las Positas College Foundation to create the Veterans Mechanical Technology Engineering Program. The two-year program works with veterans, among others, to move them from very basic math skills to calculus-ready using a cohort-style learning environment. Students can participate in summer internships and get matched with mentors at local companies, including Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

"It’s been a very successful program. I think the Lab is one square mile of heroes," Pico said. "The enthusiasm from people at the Lab who are willing to serve as mentors and open up pathways for people entering the technical workforce has just been phenomenal. I get to do it as an ambassador of the Lab and also as a volunteer to help veterans and others enter a technical career pathway."

Pico was able to combine more than 30 years of volunteering experience for different nonprofit organizations, with his government sector familiarity and academic sector knowledge to shape the program. It has been called the model for other programs that depend on schools, counties, nonprofits and companies working together.

"Volunteering to me is really about helping your community. I absolutely see myself in them. I never thought I’d have the funds to go to college. When a program came along that I could go to college, I was able to excel. So the same renaissance that I had as a young person, I see it in these people. It’s an academic vocational rebirth."

The program is set up to continue the style of team-based learning that veterans are used to. Students help each other master concepts and create a supportive community. The familiar style also helps veterans navigate the transition from military to civilian life at the Lab, especially working on multi-disciplinary projects. Pico would like to see programs like this expand across the country to other national laboratories partnering with community colleges.

"The students’ dreams have changed. Their aspirations in the STEM field have gone from just scratching the surface to talking about Ph.D.s now. That’s a wonderful moment," Pico said. "It makes you want to continue to do this; it’s the right thing to do."

Bill Dunlop felt a similar calling at a Livermore Valley Unified School District meeting in 1991. K-12 schools were facing a budget crisis deep enough to threaten all sports programs and cut music program funding in half. A group of LLNL employees headed by Dunlop and Dave Conrad decided to set up the Livermore Valley Education Foundation (LVEF) to provide the missing funds. Dunlop and his wife, a choir teacher, had their daughters enrolled at Livermore High School and involved in music, while Conrad’s kids were at Granada High School participating in sports. Together they ensured music and sports programs’ needs were met across the city.

In six months, they raised $125,000. "It was a herculean effort," recalled Dunlop, who works in nuclear forensics. The foundation reached a $4 million milestone of school funding and also works with local groups such as the Livermore Wine Association to provide matching funds for projects.

"We’ve always found that no matter how much money we raise, we still don’t have the level of services and activities in the schools that we’d all hope for," Dunlop said. "Schools are always budget limited, and we try to make that less of a limit. We try to make it better than it otherwise might be."

The organization is unique in its policy to limit operational expenses to 1 percent of the money donated, so 99 percent goes to the schools. Dunlop’s dedication to LVEF included writing the foundation’s annual reports even during the two years he spent in Geneva working on the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty. After retiring from the Laboratory in 2004, Dunlop served on the school board for 10 years, a decision that grew out of working on education issues through LVEF.

"It’s important that we provide every young person with a really good opportunity to get a good education and be successful, no matter which school he or she attends," Dunlop said. "We try as hard as we can."

Contact

Kate Hunts[email protected]

925-422-1322

Related Links

Livermore Valley Education FoundationLas Positas College Foundation

Tags

HOME CampaignCommunity Outreach

Featured Articles