From grassland to 21st century science

(Download Image)

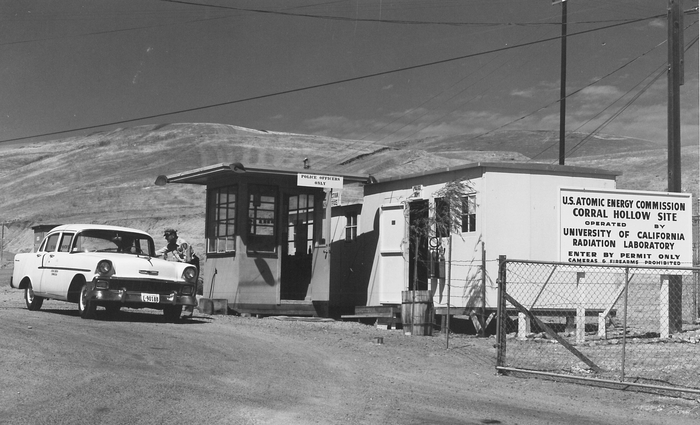

The entrance to Site 300 along Corral Hollow Road circa 1955.

(Download Image)

The entrance to Site 300 along Corral Hollow Road circa 1955.

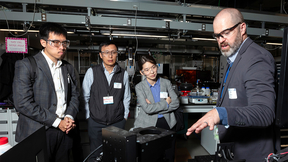

Sixty years ago, the UC Radiation Laboratory began testing high explosives at what would become one of the nation’s most sophisticated non-nuclear weapons testing sites, an 11 square-mile plot of rural grassland tucked away in the steep ravines and tawny rolling hills near the Alameda-San Joaquin County line.

On Thursday, Site 300 celebrated its 60th anniversary, with a picnic attended by more than 100 of the facility’s past and present employees, along with some special guests.

Surrounded by private cattle ranches, the grasslands that would later become Site 300 began humbly, with a few rudimentary bunkers (including a dirt-covered Quonset hut) and plywood buildings. In those heady early days the 7,000-acre expanse was an outpost for cutting-edge experimentation, sought after for its remote, rugged locale and proximity to the new Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory located just 15 miles away, according to Site 300 Manager John Scott.

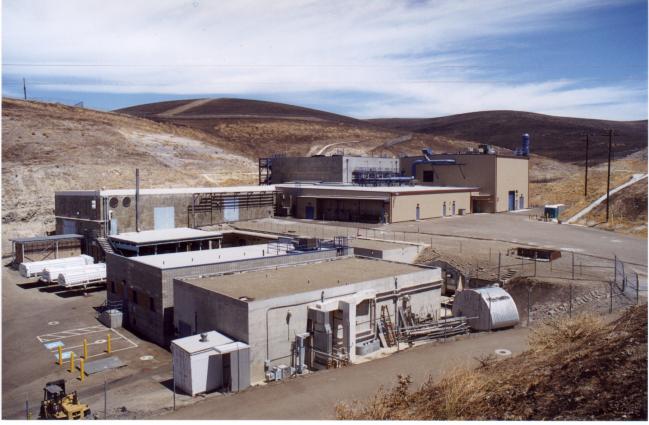

Deriving its moniker after the Lawrence Berkeley (Site 100) and Lawrence Livermore (Site 200) national labs, throughout the ensuing decades the "one-stop shop" has been the testing facility for several advanced conventional weapons, demolition munitions and even a hydrogen gas-powered "space gun" — the Super High Altitude Research Project (SHARP), designed to shoot projectiles into Earth’s orbit. At its peak, Site 300 had more than a dozen outdoor firing sites, carrying out nearly 1,000 shots a year. Today, it averages about 100 annual tests at one outdoor pad and the Contained Firing Facility (CFF).Many of the roughly 130 structures that dot the mostly barren landscape are holdovers from the site’s early days, either left to the march of time or repurposed. Since 2002, the site’s first structure, Bldg. 801, is home to the CFF, the largest indoor testing facility in the world. Another state-of-the-art facility is the newly refurbished Bldg. 836, the Engineering and Environmental Test Facility.

"It really is the key to the whole place," Scott said. "There’s nothing like it anywhere else on the globe. The air and water that comes out of the chamber after a test is not contaminated in any way. That’s a huge selling point."

A concrete box with 6-foot-thick walls lined with armored steel plating, the Contained Firing Facility can absorb a blast of up to 132 pounds of high explosive without damaging the building or negatively affecting the outside environment. It not only plays a key role in supporting the Lab’s mission of stockpile stewardship, but also is one of the main reasons why Site 300 has been able to continue its legacy. When it marked its half-century anniversary in 2005, there were rumors of a potential closure. However, in the end, the site was recognized for its uniqueness and continued relevance.

"Our contributions have been significant during the course of the time we’ve been here," Scott said. "When we had the 50th anniversary, it wasn’t clear we were going to have a 60th, but here we are."What separates Site 300 from other testing facilities, Scott said, is its ability to provide data on all the components of a nuclear weapon — with the exception of the nuclear material itself — providing researchers with valuable information about the lifespan of the country’s aging stockpile and how the weapons might react in any number of possible scenarios.

"There’s not really a great appreciation for how long it takes to prepare for a test and clean up afterward," Scott said. "We’re looking at fractions of a microsecond, so we absolutely have to be precise in what we do. There’s no second chance."

Many of the explosive devices detonated at Site 300 are fabricated and assembled on-site in facilities made for pressing, mixing and casting the raw materials. There are radiography labs for determining the stability of the explosives with X-rays, machining and assembly work bays, buildings housing state-of-the-art diagnostics and of course, the testing facilities themselves. The Lab’s High Explosives Applications Facility (HEAF) develops much of the "recipes" for the devices and the remainder of explosives used at the site.

In addition to the half-dozen tests performed at the CFF, an average of 40 to 50 explosives are detonated each year at the site’s outdoor firing facility.

However, the work done at Site 300 must be balanced with protecting the area’s fragile ecosystem. Designated as a critical habitat, the area is home to coyotes, deer, bobcats, golden eagles, red-tailed hawks and threatened or endangered species such as the California red-legged frog, California tiger salamander, San Joaquin kit fox, Alameda whipsnake and the large-flowered fiddleneck. Access to these habitats is tightly regulated and highly controlled — only about 5 percent of the entire site is developed in any way. After the Department of Energy began investigating contamination at Site 300 in 1981, extensive remediation efforts also have been made to clean up the site’s soil and groundwater, including 21 extraction and treatment systems and more than 800 monitoring wells.

Safety is of utmost importance to the site’s 130 permanent employees and their supervisors. Site 300 also has its own Alameda County Fire station and 80 miles of fire trails, which come in handy for battling the occasional wildfire. Controlled burns are done once a year to mitigate the potential of wildfires.Some structures, overgrown by weeds and rust, are monuments to Cold War-era history, such as the abandoned Advanced Test Accelerator (ATA), which at one time housed components of the Reagan Administration’s "Star Wars" space-based weapons system. As the largest structure at Site 300, it could be refurbished and used in the future, Scott said.

Through the National Nuclear Security Administration’s life extension program (LEP) for nuclear weapons and the potential for future funding for new improvements, Site 300 will continue to be an integral component to the Lab’s stockpile stewardship mission for years to come."We’re not going out of business," Scott said. "We’re going to see a lot more work than we do now, and we’re going to continue to do 21st century science into the future."

Contact

Jeremy Thomas

Jeremy Thomas

[email protected]

(925) 422-5539

Related Links

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory interactive timelineSite 300

Site 300 Keeps High-Explosives Science on Target

Site 300 Contained Firing Facility

Tags

Nuclear deterrenceStockpile stewardship

Defense

Strategic Deterrence

Featured Articles