Geothermal energy program heats up

Twenty years ago, Lawrence Livermore National Lab had a thriving geothermal program. But as funding dwindled, the program did as well.

But thanks to a new flow of money from the Department of Energy Geothermal Technologies Program Office, the LLNL research will soon flourish again.

Earlier this year, DOE issued a call for proposals. Each national lab was allowed to submit four proposals and Livermore had three out of four proposals selected for funding. Each program will receive from $400,000 to $600,000 each year for three years. Under the Recovery Act, DOE's Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy has received $400 million to invest in geothermal research.

"We've worked really, really hard to get here," said Jeff Roberts, LLNL geothermal program leader. "The program was cut significantly in the past because geothermal energy production wasn't necessarily a priority. But last summer, oil prices were high, climate change is being considered more seriously and there is a strong interest in renewable energy, especially wind and geothermal. "

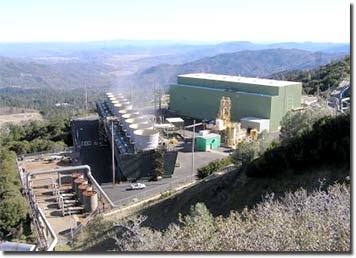

Geothermal power is extracted from heat stored in the earth. Though it has been used directly for space heating and bathing since ancient roman times, it also is used to generate electricity. A significant aspect of geothermal power is that it is a baseline power that isn't intermittent like wind or solar.

For Charles Carrigan, the funding means he can use codes that were originally developed for the weapons program and apply them to developing predictive models to determine the permeability of rock formations that supply heat for energy production by injecting and extracting fluids through wells in those formations.

"This will tell us how we can manipulate the subsurface region so wells can be more effective suppliers of heat from deep rock formations, and in turn, more productive sources of geothermal energy," Carrigan said.

Carrigan's project will focus on developing realistic computer-based models of enhanced geothermal system (EGS) stimulation-response scenarios. EGS is the creation of an effective subsurface heat exchanger for power generation when the natural system is hot enough but there is insufficient fracture permeability. The simulations are aimed at assessing the influence of many EGS properties, such as rock formation mechanical characteristics, initial thermal and stress state of the targeted rock formation, hydraulic and explosive modes of fracture propagation, among others.

"Our models will be used to explore not only the local effects of stimulation near a single well bore, but also how the stimulation of multiple wells, spaced across the reservoir, will influence heat transfer," Carrigan said. "Our hope is that these models will provide insight into selecting the best choices for producing long-term permeability enhancement on a site-by-site basis and make us less dependent on fossil fuels."

Postdoc Dennise Templeton will be using the funding for her project to map microseismicity for geothermal reservoir management.

The project is aimed at detecting and locating microearthquakes induced by EGS hydrofracturing and fluid reinjection operations within the reservoirs.

"Accurate identification and mapping of the large numbers of microearthquakes caused by geothermal production can provide us with diagnostic information so we can determine the location, orientation and length of underground crack systems for reservoir development and management applications," Templeton said.

In EGS, water is initially pumped into the ground at high pressures. Templeton said when this fluid is pumped underground, cracks form, which enhances the existing permeability of the rock.

After the underground fracture network is developed, cold water can be reinjected at lower pressures, heated by the host rock, and extracted from a production well as extremely hot water.

The underground heat can be pumped to the surface and then converted into electricity. Using seismic tools, she and her team can locate where the cracks are initially forming and the possible locations of the reinjected fluids by tracking the microseismicity.

Phase II of her project will take data generated at existing geothermal locations and conduct the seismicity analysis in real time.

Geochemist Susan Carroll will use the program funding to determine what effect geochemical reactions have on the use of carbon dioxide (CO 2 ) as an efficient heat exchanger for geothermal energy production.

"We want to understand what impact CO 2 would have on geochemical reactions and how it would affect the field, whether it would enhance or clog fracture networks that bring heat to the surface," she said.

Earlier research has shown that using supercritical CO 2 instead of water as a heat transfer fluid yields significantly greater heat extraction rates for geothermal energy. If this technology is implemented successfully, it could increase geothermal energy production and offset atmospheric emissions of greenhouse gases. But the impact of geochemical reactions between acidic waters in equilibrium with supercritical CO 2 and the reservoir rock have not been assessed.

Carroll's project consists of three phases: assessing the geochemical impact of CO 2 on geothermal energy production by analyzing the geochemistry of existing geothermal fields with elevated natural CO 2 measuring realistic rock-water rates for geothermal systems using laboratory and field-based experiments; and developing reactive transport models using the field-based rates to simulate production scale impacts, if any.

"If CO 2 is a better heat exchanger we'd be using a greenhouse gas to produce energy that is carbon free," Carroll said.

DOE's budget for geothermal energy has fluctuated during the last decade going from about $22 million per year, down to $5 million in 2007 and then bounced up to $44 million this year.

"People have realized that climate change is a real issue," Roberts said. "Everything has changed to work in favor of getting more renewable energy moving forward."

Contact

Anne M. Stark[email protected]

925-422-9799

Related Links

DOE Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy/Geothermal Technologies ProgramMining Geothermal Resources

LLNL researchers capture three tech transfer awards