A computer code led to entrepreneurial success

(Download Image)

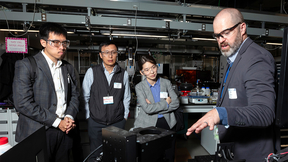

John Hallquist invented a computer code called DYNA3D, which has helped him become one of the Lab's most successful entrepreneurs as the CEO of a multinational corporation. Photo by Julie Russell/LLNL

(Download Image)

John Hallquist invented a computer code called DYNA3D, which has helped him become one of the Lab's most successful entrepreneurs as the CEO of a multinational corporation. Photo by Julie Russell/LLNL

Editor's note: This article is part of an occasional series about LLNL entrepreneurs.

John Hallquist knew it was a game changer when he invented a small computer code to analyze the structures of bombs dropped by U.S. Air Force jets.

It was 1976 and Hallquist was a young engineer who had joined Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory after getting his Ph.D. from Michigan Technological University. Working in the Lab's Nuclear Explosives Engineering Division, he was tasked with developing a software with 3D capabilities for supercomputers to measure the impact loads and structural response of bombs dropped at low altitudes.

"There was no software available at that time in the national labs that could do the job," Hallquist said.

So he invented a 5,000-line computer code called DYNA3D. Thirty-eight years later that computer code has helped Hallquist become one of the Lab's most successful entrepreneurs as the CEO of a multinational corporation.

Commercial appeal

The bomber program that used DYNA3D to measure impact was eventually cancelled. That's when Hallquist realized the commercial potential for his code, which he believed could do many 3D simulations for industries beyond the military.

What he did next helped Lawrence Livermore gain more prestige and began his journey from government researcher to successful businessman. He released DYNA3d as open source, putting the source code in the public domain in 1978.

"The reason I got DYNA3D out there was to educate as many people as possible about the technology," Hallquist said. "It allowed people worldwide to do simulations using the software with no license fee. Additionally, I felt it would bring LLNL a lot of well-deserved recognition."

The public domain allowed many companies to use DYNA3D for a variety of applications. One was crash-test software to analyze the impact of vehicle crashes for automakers in their quest to meet regulations from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) and insurance companies.

A lot of companies began developing DYNA3D for industrial use, but Hallquist did not. That's because developing the software for commercial purposes did not fit into the Lab's mission space. But Hallquist knew DYNA3D would revolutionize the auto industry, so he wanted to lead the effort.

Leaving the Lab

Hallquist decided to take a big risk and leave the comfort of LLNL to start his own company to compete with DYNA3D rivals. He began by doing consulting work before finally leaving in 1989.

"If I hadn't left, the French would have a monopoly on crash-test software," he said. "In two years, it would be hopeless to develop competing software because companies don't change software very easily. It can take years before they switch an engineering code."

Hallquist founded the Livermore Software Technology Corporation (LSTC) with one employee: himself. Its initial goal was to provide consulting work and further develop DYNA3D into superior crash-test software, which the company would eventually call LS-DYNA.

The software uses 3D modeling toaccurately predict a vehicle's behavior in a collision and the effects of the collision on its occupants. It enables automotive companies and their suppliers to test car designs without having to tool or experimentally test a prototype, thus saving time and money. LS-DYNA would eventually be widely used by the automotive industry to analyze vehicle designs and prototypes for testing.

"You couldn't do the vehicle designs today with the current requirements from NHTSA without doing countless simulations," said Hallquist, adding that LS-DYNA also could be used in other industries.

Back then, LSTC started with six initial customers: General Motors, Mercedes-Benz, Porsche, Lockheed-Martin and Alcoa. The company was mostly doing consulting work for its customers, not licensing the software.

Today, LSTC is a multinational corporation headquartered in Livermore with 70 employees worldwide and a customer base of 2,500. It now licenses software to its customers, instead of doing consulting for them.

"We are dominant now," Hallquist said.

A recent study by the nonprofit Council on Competitiveness in Washington, D.C. found that the use of DYNA3D or DYNA-like programs saves U.S. industry about $14 billion annually by significantly reducing the number of automobile crash tests that need to be performed to improve the crash worthiness of cars

Multiple applications

In the auto industry, LS-DYNA is used for analyzing specialized automotive features such asseatbelts, slip rings, pretensioners, retractors, sensors, accelerometers, airbags, test dummy models and inflator models.

LS-DYNA also is widely used in the metal forming industry. It accurately predicts the stresses and deformations experienced by the metal, and determine if it will fail. The software supports adaptive remeshing and will refine the mesh during the analysis, as necessary, to increase accuracy and save time. The applications include metal stamping, hydroforming, forging, deep drawing and multi-stage processes.

The aerospace industry uses the software to simulate bird strikes, blade containment and structural failure. NASA uses it to simulate flight re-entry.

"Most jet engine manufacturers use our software worldwide," Hallquist said. "Rolls-Royce is a big customer."

Other LS-DYNA design and manufacturing applications include drop testing, sports equipment, offshore platforms, pavements, failure analysis, earthquake engineering, metal cutting, biomechanics, plastics, glass forming and electronic components.

"LS-DYNA has really shaken up the market for analysis software," Hallquist said. "It forced everyone to compete with us. We are continuing to add more physics to it for the future."

Sage advice

Being an entrepreneur often requires taking risks and being willing to live a different lifestyle. Now that Hallquist has enjoyed enormous success in his chosen path, he's got advice for others.

"If you decide to do it, always have a fallback position with a company that you know will hire you," he said. "I figured if I failed, I would have moved to Detroit to work for an auto supplier."

Compared to the Lab, being an entrepreneur means working long hours. Eighty-hour weeks are not uncommon. Hallquist said it's very important that your family is understanding and supportive of the long hours.

Moreover, hiring the right people for your company is critical, although finding them can be challenging.

"The main problem is finding qualified people," he said. "If they are good, they will be well compensated and won't leave the company they are working for."

Finally, being an entrepreneur has many rewards, he said, including the freedom to do what you want.

"You can try out things you have a strong interest in without anyone second guessing you," he said.

Related Links

John HallquistLivermore Software Technology Corporation

LS-DYNA

National Highway Traffic Safety Administration

Michigan Technological University

Council on Competitiveness

Tags

HPC, Simulation, and Data ScienceComputing

Engineering

Science

Featured Articles