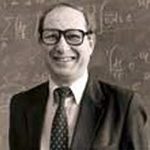

Arthur Kent Kerman

Arthur Kent Kerman, professor emeritus of physics and a distinguished international researcher in MIT’s Center for Theoretical Physics and Laboratory for Nuclear Science, died May 11. He was 88.

Kerman was known for his work on the theory of the structure of nuclei and the theory of nuclear reactions.

“He was a wonderful friend and colleague, accomplishing many important things in the creation and promotion of science,” said Professor Emeritus Earle Lomon of the CTP, and Kerman’s longtime friend. “We will greatly miss his friendship and guidance.”

As Mike Campbell of the University of Rochester so poetically said: “The world is a little more empty and quiet without Arthur in it.”

Kerman was born May 3, 1929, in Montreal. He graduated in 1950 from McGill University, where he studied physics and mathematics. At MIT, under Victor Frederick Weisskopf, he completed his Ph.D. in nuclear surface oscillations in 1953. From 1953-1954, he studied with R.F. Christy at the California Institute of Technology under a National Research Council Postdoctoral Fellowship, and in 1954 he began a two-year stay at the Institute for Theoretical Physics in Copenhagen.

“With the presence of Niels Bohr, Aage Bohr, Ben Mottelson and Willem V.R. Malkus, there were many physicists from Europe and elsewhere, including MIT’s Dave Frisch, making the Institute for Physics an exciting place to be,” recalled Lomon. Kerman’s close friend since the early 1940s, when they were Boy Scouts in Montreal, Lomon studied with Kerman at McGill, MIT and Copenhagen.

Kerman’s research included nuclear and high-energy physics, astrophysics, and the development of advanced particle detectors. His interests in theoretical nuclear physics included nuclear QCD-relativistic heavy-ion physics, nuclear reactions, and laser accelerators.

Kerman published or co-published more than 100 papers. He wrote papers on the effects of the Coriolis interaction in rotational nuclei; quasi-spin; the application of the Hartree-Fock method to the calculation of the ground state properties of spherical and deformed nuclei; pairing correlations in nuclei; and the possible existence of transuranic islands of stability. In his research on reactions, his papers discussed the scattering of fast particles by nuclei. He also wrote papers on intermediate structure in nuclear reactions; on the properties of isobar analog states; and strangeness analog resonances. He was an early advocate of the importance of quarks for understanding nuclear physics. He developed a nucleon-nucleon potential with a soft core that fits nucleon-nucleon scattering data as well as potentials with a hard repulsive core do, which was found to be useful in the study of what is needed beyond scattering data to determine the properties of nuclear matter and finite nuclei.

Kerman joined the MIT faculty in 1956 as an assistant professor of physics. In the summers of 1959 and 1960 he was a research associate at the Argonne National Laboratory, and during this period he also was a consultant to the Shell Development Company of Houston, and the Knolls Atomic Power Laboratory. He also participated in the Physical Science Study Committee — a group of high school and university physics professors — to write a more accessible and engaging high school physics textbook. He was a consultant with Educational Services Inc. from 1959 to 1966, and collaborated in the quantum physics part of the experimental course Physics: A New Introductory Course (nicknamed PANIC), produced by the Education Research Center at MIT. He became an associate professor in 1960, and the following year, he went on academic leave and was “professeur d’echange” at the University of Paris under a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Fellowship. He became professor in 1964.

In the early 1960s, Kerman traveled with physics professors Sheldon Glashow, then of Berkeley and now of Boston University, and Charles Schwartz of UC Berkeley for a month-long visit as potential members to JASON, a scientific advisory group in Washington, D.C., sponsored by the Department of Defense and the Department of Energy, among other government groups.

“We were asked at the beginning of our particular interests,” recalled Glashow. “What they were getting at was whether we wanted ‘war’ work or ‘peace’ work. Everybody, except us three ‘lefties’ including Arthur, chose ‘war.’ Our ‘peaceful' challenge was to examine all available sources, whether classified or not, to assess the potential value of airborne or satellite surveillance of the Soviet Union and to produce a supposedly unclassified document. We did our work, and our document was promptly classified. We never heard back from JASON, nor did we care.”

Kerman’s research included nuclear and high-energy physics, astrophysics, and the development of advanced particle detectors. His interests in theoretical nuclear physics included nuclear QCD-relativistic heavy-ion physics, nuclear reactions, and laser accelerators. He developed a set of nucleon-nucleon potentials, which were found to be useful for the study of nuclear matter and finite nuclei.

From 1976-1983, he was the director of MIT’s Center for Theoretical Physics, and from 1983-1992, he was director of the Laboratory for Nuclear Science. For many years, Kerman was a leading force in pushing for new initiatives in science. He had various longstanding consulting relationships with Argonne, Brookhaven National Laboratory, Knolls Atomic Power Laboratory, Lawrence Berkeley, Lawrence Livermore, Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory, and Oak Ridge national laboratories, and with the National Bureau of Standards (now NIST).

Kerman advised 43 students, from 1958 to 2006. He officially retired from MIT after 47 years and retained the title of professor emeritus from 1999 until his .

Many described Kerman as an outspoken advocate in his field. “He never hesitated, regardless of the consequences, to speak out and to support me when called upon in different circumstances to analyze programs that involved large-scale funding while lacking adequate justification,” said MIT physics professor Bruno Coppi, Kerman’s friend since the 1960s. “We both had to take a public stand, and time proved that our assessments were correct.”

“He was, until the end, a valued advisor to different national laboratories and to the highest levels of the Department of Energy,” said Coppi.

“Arthur either knows everyone of importance or had them as students. I continue to be amazed at his ability to get appointments with everyone in DOE or at the laboratories … If you want something done, convince Arthur and he’ll be an influential advocate.”

Kreisler added, “Whenever you work on an exciting new science project, Arthur is sure to tell you that he was involved in the very early stages of that project. While it sometimes seems impossible for him to have actually done as much as he says, I know from experience that it really is true.”

However, Kerman was known for his calm, quiet style of leadership. “He had an extraordinary capacity to think on his feet, inspiring collaborators,” said Lomon. “Although, he had much less interest in writing papers, which was a source of some frustration to the same collaborators.” Kerman kept frequent contact with his friends and collaborators, despite his declining health. Kerman was coming regularly to weekly physics department lunches. “He delighted in reminiscing about the special atmosphere we had in our department during the times of the ‘Copenhagen Table,’” said Coppi, who met weekly with Kerman, up until a week before his passing away.

Despite health problems in his later years, his commitment to physics and service to the country still saw him traveling all over the world, as well as back to campus, well into his 80s. Until several days before he died at age 88, he was working with Mark Mueller on a new theory of dark matter and energy.

“In recent years Arthur was deeply concerned about the trends in funding and management of research, and of physics in particular, both at the national and international level,” said Coppi. “Arthur will be greatly missed at MIT, in our department, and in the international scientific community.”

A long-time resident of Winchester, Mass., Kerman was married to Enid Ehrlich for 64 years. He is survived by children Ben, s an MIT ’81 biology alum and physician at Brigham and Women's Hospital, of Hingham; Dan, mechanical engineer at the Federal Aviation Administration, of New Hampshire; Elizabeth ,an architect, of San Francisco; Melissa, an arts and crafts business owner, of Charlotte, North Carolina; and Jaime, who works at Lincoln Lab, of Arlington, Massachusetts. Kerman is also is survived by 11 grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.

Gifts in Kerman’s name may be made to the Arthur Kerman Fellowship Fund, #3302540. This gift will support fellowships in the Physics Department, with a preference for fellows conducting research in theoretical physics. For more information, contact Director of Development emcgrath [at] mit.edu (Erin McGrath) at 617-452-2807.

A memorial service will be held 1-5 p.m., on Friday, Oct. 6, 2017. It will take place at the Pappalardo Room, 4-349, 77 Massachusetts Ave., Cambridge, MA 02139. See the web for the invitation. The service will begin at 1 p.m. with opening remarks. There will be a series of talks and remembrances by colleagues and family members. There will be a break at 2:30 p.m. and then a reception starting at 4 p.m. For those unable to attend, written sentiments can be sent to Scott Morley at morley [at] mit.edu (morley[at]mit[dot]edu) for inclusion in a book for Arthur's family.